The circular economy and sustainable urban planning

The circular economy and sustainable urban planning

In response to the global environmental challenge, particularly the climate crisis, a new economic paradigm is emerging in all sectors, called the “circular economy”. In this Insight paper, Brussels studio Director Mariia Grachova examines the role of architects and others in implementing the principles of the circular economy in the developments we create, as well as looking at strategies for doing so.

What is the circular economy?

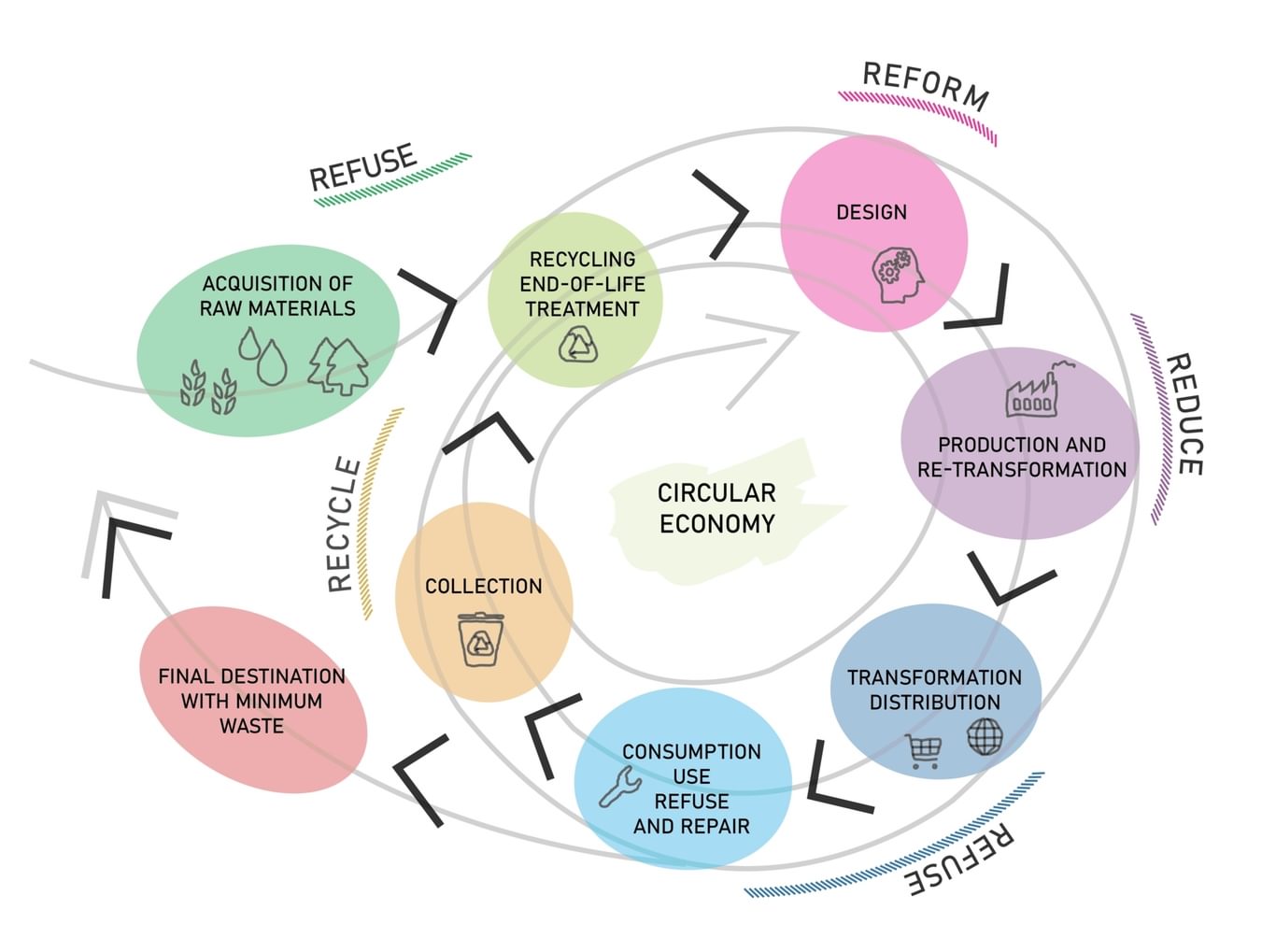

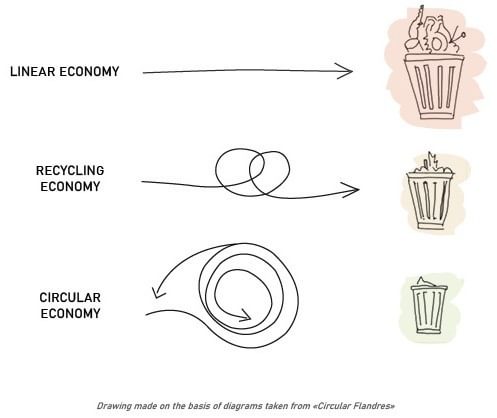

At its simplest, the circular economy is about eliminating waste in the long term, not just the short. The idea is to improve on the advances made by the recycling economy, which has aimed to maximise the re-use of materials before finally disposing of them, so that there is no disposal at all, just continuous re-use.

The great challenge of future urban development is to transform our disposable society into a circular economy where as little as possible is wasted and recycling is permanent process. As the property development sector has historically been a major contributor to global CO2 emissions, the principles of the circular economy must be at the heart of the future direction of the industry, including in the way we plan our urban spaces.

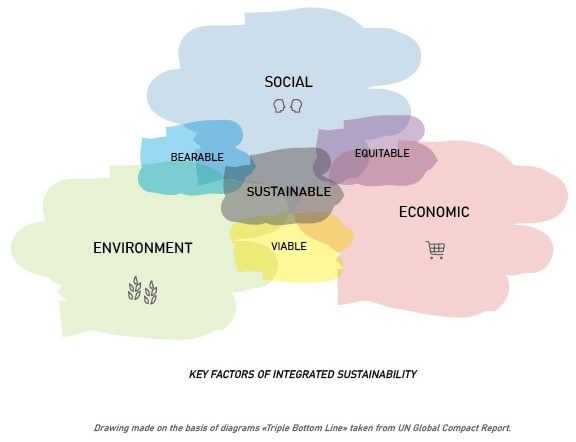

When we envisage how our urban designs can be made truly circular, we need to take account of social and economic sustainability, as well as the environment. This broader concept of sustainability has guided Chapman Taylor in the development of its vision for Responsible Design, considering not just the environmental impact, but also the human and social impact.

The focus in design and construction must shift towards mitigating or improving the impact we have, including how we design/plan for use cycles, flexibility, disassembly and the ease of recycling.

The role of the architect / urban designer

The way in which we, as designers, envisage a built environment in response to a client’s brief and the development’s context is crucial to embedding them within the circular economy. Decisions made during the specification and design processes can create a positive ripple effect, in terms of sustainability, throughout the construction industry. Achieving sustainability in our buildings requires us to design in a way which helps reduce or eliminate waste – not just in terms of the materials we use to build and maintain our buildings, but also in terms of the buildings themselves and their long-term resilience, particularly their adaptability for future uses.

The question for architects is how to implement the principles of the circular economy when faced with the functional transformation of existing buildings and also with the transformation of whole neighbourhoods.

On every project we create, we start by considering the environment within which our buildings will sit. Every development has a unique hinterland and, if it is to be part of the circular economy, we must gain a deep understanding of the wider context and the ways in which the development will interact with it in the future.

We can often meet our clients’ briefs, including on quality and costs, and yet still work within the parameters of circular economy principles. This sometimes means thinking much further ahead than the client has, which is not always easy.

However, architects and urban designers cannot do it all on our own; we should always try to involve our clients, partners, other stakeholders and the end users of the spaces we create. We need to be advocates for the principles behind the circular economy so that others will too, helping to spread the concept much further and to ensure that the principles have new guardians into the future.

The importance of flexibility

The principles of the circular economy can dovetail with the self-interest of developers and others. Much of the approach is merely common sense; we want to design in ways which future-proof the buildings and spaces we create, providing maximum flexibility (and thus reducing lifecycle costs, including the need for extensive retrofits).

The market, and people’s lives, are changing at a rapid pace, often in ways which would have been impossible to predict just 20 years ago, so flexibility and easy adaptability to different formats and uses is simply good business sense; the long-term savings and benefits could become very apparent much sooner than anticipated.

Chapman Taylor’s experience in the modular/off-site construction sector has convinced us of the benefits that modular construction can bring in terms of resilience, adaptability and reducing waste. For example, as much as 50% of waste on traditional building sites could be prevented by a switch to off-site construction. Ideally, the construction would take place on or near the site.

Our Umbrellahaus® modular prototype is ideally suited for thinking about future adaptability and repurposing, allowing buildings to be reconfigured in response to changed requirements. The space that is freed up can be repurposed, maximising efficiency and circularity.

Wellbeing and the ecosystem

One key environmental benefit of adopting these principles can be felt very early on – by recycling materials, particularly those which are locally sourced, the need for transportation of heavy loads is reduced or eliminated. This reduces carbon emissions and air pollution while keeping costs down.

The collection, storage and use of rainwater and the reuse of grey water is another element of a circular strategy, as is the use of renewable energy. Chapman Taylor has worked on many projects worldwide for which renewable energy and recycled water are key components of their sustainability credentials. We have also been working on several masterplans in China that incorporate Sponge City principles, and we are seeing these water management concepts gaining ground in Europe and beyond.

An important aspect of the circular economy approach to urban design is to put limits on urban sprawl, emphasising increased density and reusing brownfield land as much as possible. We need to make use of what already exists, to the extent that we can, rather than using new land unnecessarily. The denser the development, the more efficiencies that can be obtained, including in energy and material use. As existing infrastructure and services can be reused or expanded, the extent to which new utilities have to be built or extended is reduced or eliminated.

Chapman Taylor aims to design for compact cities in our urban design projects, particularly those planned for 15-Minute Living. These are urban districts designed so that the key amenities that a person needs can be found within a 15-minute walk of where they live or work, and with those functions placed intelligently so that shorter journeys are for more regular trips.

The more urban design projects which take this approach, the greater the benefits for the planet and for the wellbeing of its people. Among the beneficial consequences are the protection of green spaces and the ecosystems within them, a reduction in air and water pollution, particularly from traffic, a great reduction of material and energy waste and improvements in people’s wellbeing as they live closer to the countryside and are less likely to be imprisoned within their cars.

Reusing the existing, reducing the need for carbon-intensive mobility and embedding nature and biodiversity are imperatives for contemporary society; our urban designs should create micro-cities within existing cities, deeply transforming the nature of modern living.

Sourcing resilient recycled materials

Measures and technologies which reduce the demand for materials or help to recover raw materials from used products are gaining importance in the light of the increasing cost and decreasing availability of raw materials and the impacts on the environment of producing or extracting them. The current shortage of timber is a good example, illustrating the importance of reducing our reliance on new materials in favour of reusing what we already have.

There are challenges in sourcing enough high-quality recycled materials, particularly if trying to do so locally, so the extent to which we can deliver a fully circular development will depend on its nature and context.

A large-scale urban design for a brand-new district or a major mixed-use scheme will not be able to rely on sourcing only recycled material – there simply isn’t enough such material of the right quality. Instead, the focus must be to use as much as possible which is available locally. Urban planning and design will increasingly focus on efforts to combine local sources, material sinks and material flows. New value chains, such as urban mining, will gain in importance for reducing waste.

There is even a case for establishing factories on or near the site so that the required materials can be created/refined and brought to site without having to rely on long-distance transport, with its attendant waste and pollution. The factories themselves must also be conceived within circular economy principles, with a plan for their future uses if not intended as permanent production facilities.

A building refurbishment or repurposing, on the other hand, can go much further than a large-scale urban development, with much of the material already on site. As we see more retail refurbishment and repurposing projects, for example, we should take stock of what is there already, whether stone, bricks, glass, wood or anything else that can be recycled, and always look for opportunities to reuse them on the project (or, if impossible, on another project).

Material resilience is crucial; the longer it lasts, the more circular the project. The material should be easy to maintain, requiring few or no interventions and thus saving on upkeep costs. The challenge is in finding resilient material which is also appropriate for the task, particularly in terms of providing the optimum scope for flexibility and easy adaptation.

This approach demands a change in mindset from designers and developers. Where once it may have been less effort to just demolish and start again completely, we must now think more responsibly, constantly looking for ways to make our projects truly circular.

In planning urban neighbourhoods, it is becoming increasingly important to take on board an integrated planning team from the outset of the design process, because choosing the right materials and coordinating the various trades are becoming increasingly important in ensuring a finished product which complies with the principles of the circular economy.

Technology and the circular economy

BIM is an excellent tool when assessing how to implement a circular economy approach to our projects. BIM can help us to properly assess the potential carbon footprint and lifecycle of the materials we use, as well as the effects of using those materials on energy use, water consumption and other sustainability performance indicators.

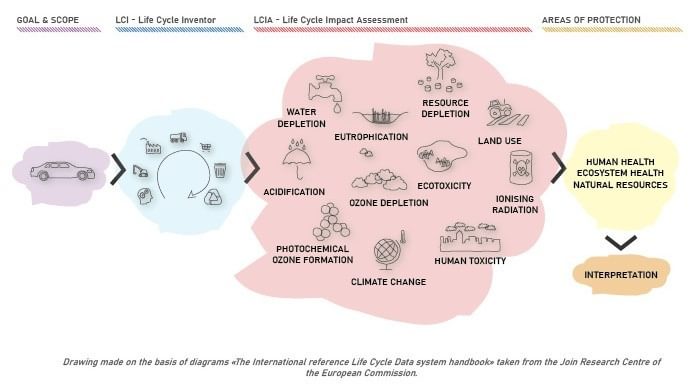

DIN EN ISO 14040 describes the entire lifecycle of product systems, including extracting or producing raw materials, processing them, using them for their intended purpose and, finally, recycling or disposing of them. For buildings, this involves systematically recording and evaluating all of the emissions and costs arising throughout the whole lifecycle of the building and doing the same for the lifecycles of individual components, such as doors, windows and walls. BIM can then automatically generate Lifecycle Assessment models, which can be useful in helping to simulate and evaluate other sustainability requirements automatically on future projects.

These were aspects of the construction process that were once too complex to fully comprehend, but BIM has made it possible to be much more discerning when choosing materials and designing for resilience within a whole life approach.

Smart building and Smart City technology is also becoming increasingly relevant, both in relation to the design of the buildings/districts and to their operation within circular economy parameters. The more data we can collect and analyse at the design stage, the more appropriate our designs can be for their locations and users, and smart technology is becoming a vital tool in that regard.

Using smart technology at the operational stage will also help to cement the circular economy credentials of the built environments we create; for example, automatically reducing energy waste and material degradation by adjusting heating, lighting, mechanical and other functions in response to building occupation.

The role of operators and end users

The success of a built environment in terms of how it adheres to circular economy principles is not fully determined once the design and construction process stops; the operators and end users have a crucial role to perform. The role of the designer is to give them the tools to be able to uphold those principles, whether in relation to how the environment is used, maintained, adapted or, ultimately, repurposed. Architects and urban designers cannot make their decisions for them; we can, however, nudge them, through design, in the desired direction.

One way in which we can do this is simply by designing new spaces or reinventing existing ones so that they can cater for a mix of uses. The buildings we create should be designed with the infrastructure and flexibility to allow us to shop, live, work and socialise within them.

In the same way that it makes no sense for us all to own cars, often using them less than a couple of hours each week, so it makes no sense for buildings to be designed with only one type of user in mind, left empty for long periods each week. The long-term sustainability and circularity of the buildings we create is better ensured by providing them with the capability of being used by different types of users throughout the day and the week, resulting in energy and material efficiencies as well as reducing wasted space.

A mixed-use approach to design will allow owners, users and operators to respond to social and market changes quickly and easily without having to face the conundrum of whether to demolish part or whole of the buildings (which is, unfortunately, what we are seeing with many redundant department stores at the moment). Enabling such flexibility is partly a responsibility of local authorities, who need to take a less restrictive and siloed approach to zoning for different functions.

Alternatively, more emphasis could be placed on relatively new types of living, such as the popular Build-to-Rent format, which brings people together within a managed and curated community environment where services and amenities are shared – again, moving away from the idea of everyone having to own their own individual swimming pool, home gym, garden or other amenities. Build-to-Rent is ideally placed to respond flexibly to changes in market or social behaviours, such as the explosion in the number of home deliveries due to online shopping, and a modular approach can be particularly useful to these developments.

Conclusion

As with sustainability-focused accreditation such as BREEAM and LEED, long-term reusability and adherence to the principles of the circular economy could soon be an automatic requirement for many clients and stakeholders, to the extent that circular economy certification will eventually become routine for many developments. It may also be a significant marketing plus for developers, adding value to the built environments they create.

The scale of the task and the potential benefits to be gained necessitate an integrated and joined-up approach from designers, developers, local authorities, infrastructure and energy providers, end users and other stakeholders. Architects and urban designers have an important part to play, but we cannot do it in isolation.

The circular economy approach to our built environment isn’t just about design, or about the social responsibility of private actors; it is about the responsibility of all humans to be better custodians of our planet than we have been so far. It is, therefore, time to work together as a society to promote and honour these principles as part of our duty towards future generations.