Repositioning outdated shopping centres

Repositioning outdated shopping centres

The past 15 years has seen the shopping centre format enter a sharp decline, exacerbated by the failure of the department stores which once reliably anchored them as well as the rise of online shopping. In this Insight paper, Group Board Director Adrian Griffiths makes the case for rethinking the once-dominant shopping centre model of monolithic, single-use, privatised town centre spaces so that our urban cores can once again serve their traditional purposes of providing a context-appropriate mix of social and commercial uses, a multi-layered experience and a strong sense of community identity.

The rise and fall of the enclosed retail monolith

The UK retail sector expanded dramatically between 1985 and 2006 as the public’s love of shopping as a leisure activity led to rapidly growing demand for new space. The rise of the brands required larger retail units, which were replicated from town to town.

Inspiration was taken from the American model, which primarily relied on department stores acting as anchors at the ends of malls, with standard retail units laid out between them. The department stores paid a minimal rent, with the value coming from the standard units. The size of these standard units continued to grow, making it challenging to fit them into historically tight urban environments.

1970s shopping centres had previously been based on the Arndale model, which was mainly single-level with no natural light to the malls, often with rooftop servicing. The new model put retail on steroids, with shopping centres becoming dominant developments with basement servicing, multi-level retail-covered malls with natural light and significant car parking, often at roof level. The centres were mainly single-use, with an element of F&B in the form of a food court, another American copy.

These schemes, particularly in their size, paid no respect to the history of the urban core, often wrapping themselves around the backs and sides of the high streets. They were also gated communities, closing in the early evening and effectively privatising large swathes of towns to their detriment. Other complementary uses were often removed from town centres to make way for these huge schemes.

These new developments were designed to meet the customer’s requirements, which was all well and good until the customer’s requirements changed. They performed well until the retail sector reached its peak in 2006, since when there has been a continuing decline in the requirement for physical retail space. Some of this vacant retail space has been repositioned as a result of the growth of the Food and Beverage market, but even this sector is now on a downward curve.

What’s wrong?

In summary, there is now too much retail space which is no longer required, primarily as a result of the growth in e-commerce and a change in the customer’s requirements.

Younger generations are much more adept at using technology to find the goods they want to purchase. They are not as cash-rich as their parents and are more selective about what they spend their money on, which may be an experience rather than a physical purchase. Socialising is important to them and they do not use department stores to the same extent their parents once did.

This change in the customer’s profile has created a huge problem. Historically, high streets have evolved on a piecemeal basis over time, with existing buildings being individually repurposed and expanded and new buildings being added to meet the growing demand.

Never before have we had such large developments built in one go in our town centres, mainly in prime locations – centres that have costs millions to create and have a huge amount of embodied carbon. The dramatic change in the customer’s requirements means that these mammoth schemes are no longer fit for purpose, but modifying them is not going to be easy. These centres, having peaked in value around 2010, have subsequently been constantly declining assets, a fact that many owners are unwilling to face. However, we should not hide from today’s true asset values because this will only hinder the required change and progress.

Change will have to take place or these centres will become a drain on finances. Many owners may just pass the keys back to the banks, which, in effect, is only passing the buck and leaving it to those banks to address these problems. The owners should not assume they need to face these issues on their own, but should rather join forces with local authorities and other key stakeholders, working together to deliver the right design and funding solution.

Correcting fundamental mistakes

Finding solutions will not be easy. No one size fits all and each project will have to be bespoke. The first principle of sustainable design is to consider whether a refurbishment/repositioning is feasible but we shouldn’t shy away from the fact that a total demolition may have to be considered. However, there has to be rhyme and reason to the solution, based on the understanding of two key principles: understanding the holistic functionality of our town centres and providing what the customer requires.

For excellent town centre functionality, we have to consider the urban design principles that make a town work as a whole.. We can no longer have mammoth, gated private developments that are not accessible by the public at certain times of the day, mostly in the evenings, dominating the cores of our town

The planning mistakes of the past have to be corrected, starting with a review of the historical street patterns to assess what needs to be repaired to reconnect the surrounding districts. New linkages will need to be considered to further break down the monolithic blocks into urban forms of a scale that suit their localities. Re-establishing a network of streets and spaces on a scale that is authentic to the place is fundamental. It is around this new urban networks that we can masterplan the uses the customers require today.

What do customers require? They require convenience goods, authentic independent retail, brands, food and beverage options, leisure, community facilities, sport, curated and pop-up retail, co-working, medical centres, aged living, care homes, hotels, residential and more. Most importantly, they require an experience. Most of these are functions our towns used to provide, working together to create a proper community.

Customers don’t require numerous department stores, retail multiples and oversized shop units, underpinning the point that we need to reduce the quantum of retail space in our town centres without losing the active frontages. Converting this retail space to other uses requires careful consideration, ensuring the mix of uses work holistically with the town centre . It is important to recognise that conversion may not necessarily be an option, with a new-build approach being the only long-term solution in many cases.

Many of these shopping centres were covered malls over two or three levels, with parking above. Solutions to be investigated include the removal of glazed roofs to create open streets, with other uses replacing the upper level retail space. Reducing the size of retail units while still retaining their active frontages can leave void space to the rear, but this can instead be used for a variety of uses, from leisure boxes to home storage units.

Conversion of some of the car parking into such uses as residential, workplace, later living, care homes and leisure boxes is also possible, while redundant department stores may accommodate retail and F&B at ground level as well as residential, student accommodation, leisure, hotels, co-working spaces, medical centres and more on the upper levels.

Ultimately, total demolition may be the only solution, and we have previously taken this approach in such cities as Canterbury, Exeter, Bath and are currently proposing it in Bolton. Other current projects envisage the demolition of 30% of the existing retail space, the introduction of a new town square of high-quality public realm, a new cinema and restaurants in a redundant department store and a 30,000m2 later living and healthcare facility.

The reduction in retail space creates the required demand tension to support the letting and rental levels for the remaining retail space. However, this process will be financially challenging and we need to work closely with the local authorities and government bodies to help with funding.

Rewriting the rules

The financial model on which these retail centres were previously appraised has to be completely rewritten. Values based on declining Zone A rents and yields are longer relevant. We need to understand the importance of sustainable rents, essentially meaning what can the retailers afford to pay, which should follow the low base rent and turnover formulas.

In reality, the only thing that really matters is how we maximise the income generated from the development through effective management – growing this on a year-by-year basis and demonstrating the development’s longevity. We must also not overlook the value of our public realm and the income, no matter how small, that can be generated from this through curation.

The art of town centre management has to be taken to the next level and will be akin to managing a resort or leisure park, taking lessons from the likes of Disney, which knows how to deliver an experience. Gone are the days when a shopping centre owner could let a retail unit on a 25-year lease, walk away and just collect the rent. Now is the time for true collaboration between the owners and the operators, both sharing in the success.

Achieving the right solution will be a challenge, but we can no longer paper over the cracks. We have to grab the opportunity and produce a form of development that is adaptable, responding quickly and inexpensively to future market forces, maintaining their relevance and ultimately standing the test of time, something their forbears failed to do.

‘City Centre South’ will upgrade several areas of the historic heart of Coventry, including Bull Yard, Shelton Square, City Arcade and Hertford Street, and will make the city a significant shopping and leisure destination in the West Midlands.

The rise and fall of the enclosed retail monolith

The UK retail sector expanded dramatically between 1985 and 2006 as the public’s love of shopping as a leisure activity led to rapidly growing demand for new space. The rise of the brands required larger retail units, which were replicated from town to town.

Inspiration was taken from the American model, which primarily relied on department stores acting as anchors at the ends of malls, with standard retail units laid out between them. The department stores paid a minimal rent, with the value coming from the standard units. The size of these standard units continued to grow, making it challenging to fit them into historically tight urban environments.

1970s shopping centres had previously been based on the Arndale model, which was mainly single-level with no natural light to the malls, often with rooftop servicing. The new model put retail on steroids, with shopping centres becoming dominant developments with basement servicing, multi-level retail-covered malls with natural light and significant car parking, often at roof level. The centres were mainly single-use, with an element of F&B in the form of a food court, another American copy.

These schemes, particularly in their size, paid no respect to the history of the urban core, often wrapping themselves around the backs and sides of the high streets. They were also gated communities, closing in the early evening and effectively privatising large swathes of towns to their detriment. Other complementary uses were often removed from town centres to make way for these huge schemes.

These new developments were designed to meet the customer’s requirements, which was all well and good until the customer’s requirements changed. They performed well until the retail sector reached its peak in 2006, since when there has been a continuing decline in the requirement for physical retail space. Some of this vacant retail space has been repositioned as a result of the growth of the Food and Beverage market, but even this sector is now on a downward curve.

What’s wrong?

In summary, there is now too much retail space which is no longer required, primarily as a result of the growth in e-commerce and a change in the customer’s requirements.

Younger generations are much more adept at using technology to find the goods they want to purchase. They are not as cash-rich as their parents and are more selective about what they spend their money on, which may be an experience rather than a physical purchase. Socialising is important to them and they do not use department stores to the same extent their parents once did.

This change in the customer’s profile has created a huge problem. Historically, high streets have evolved on a piecemeal basis over time, with existing buildings being individually repurposed and expanded and new buildings being added to meet the growing demand.

Never before have we had such large developments built in one go in our town centres, mainly in prime locations – centres that have costs millions to create and have a huge amount of embodied carbon. The dramatic change in the customer’s requirements means that these mammoth schemes are no longer fit for purpose, but modifying them is not going to be easy. These centres, having peaked in value around 2010, have subsequently been constantly declining assets, a fact that many owners are unwilling to face. However, we should not hide from today’s true asset values because this will only hinder the required change and progress.

Change will have to take place or these centres will become a drain on finances. Many owners may just pass the keys back to the banks, which, in effect, is only passing the buck and leaving it to those banks to address these problems. The owners should not assume they need to face these issues on their own, but should rather join forces with local authorities and other key stakeholders, working together to deliver the right design and funding solution.

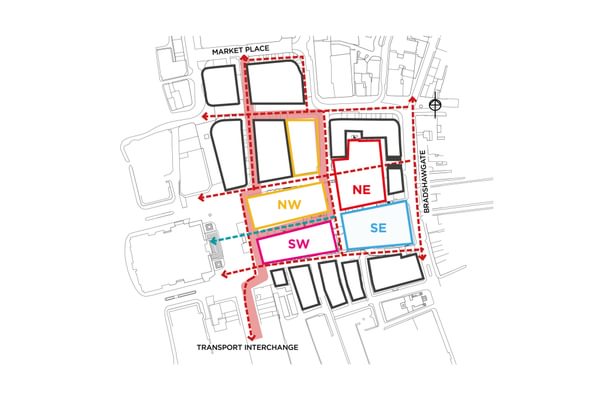

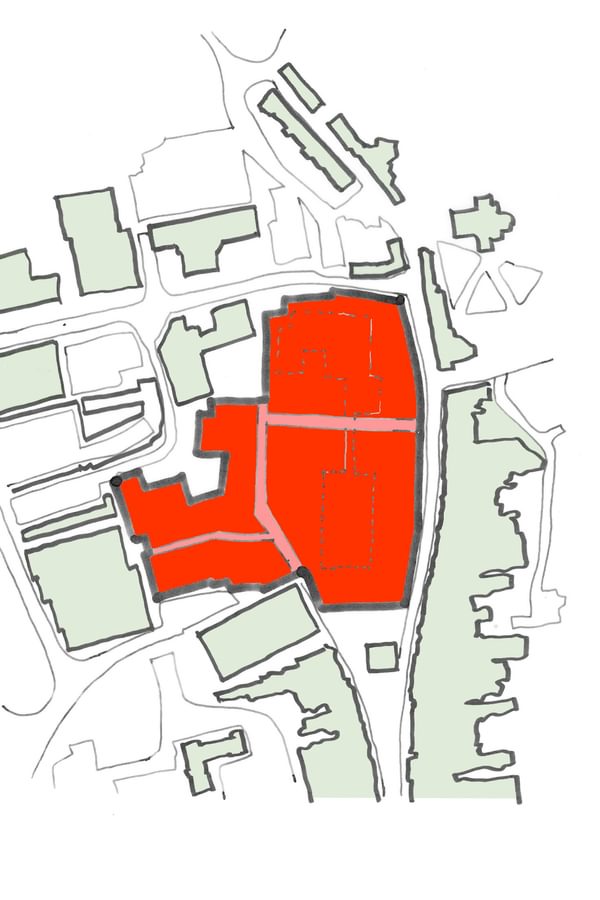

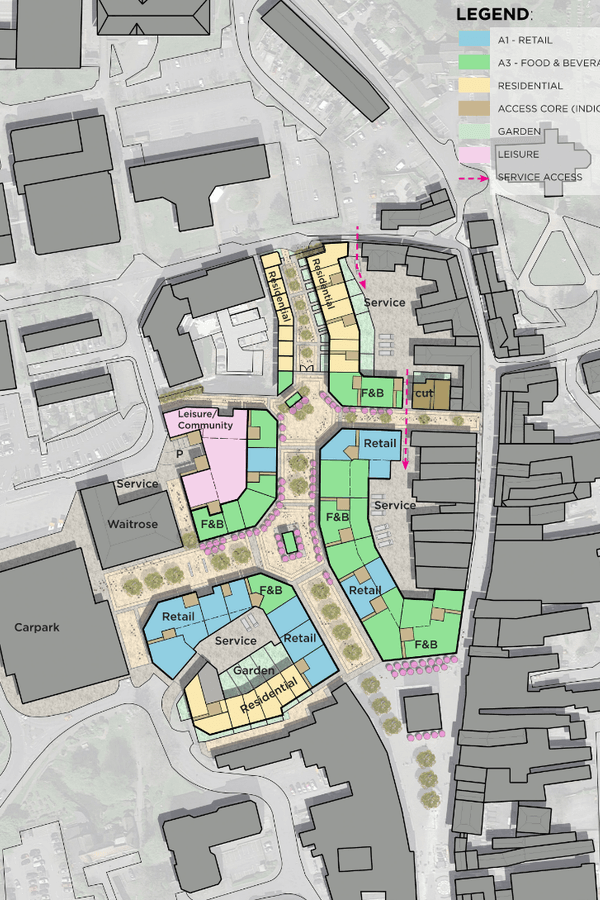

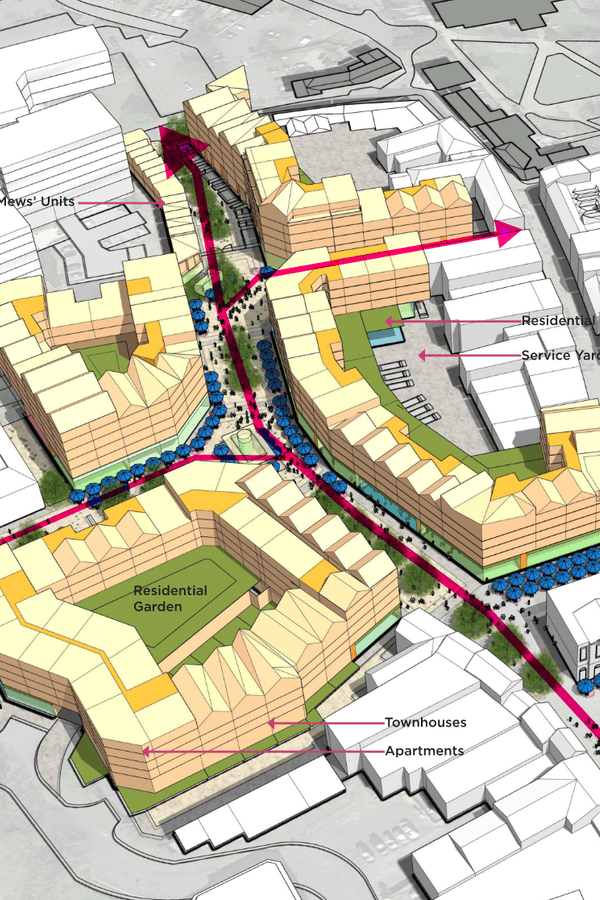

Before and after: Crompton Place Bolton, the 1970s shopping centre obliterated the historic urban fabric and the new proposal for a mixed-use scheme was awarded planning permission in 2020

What’s wrong?

In summary, there is now too much retail space which is no longer required, primarily as a result of the growth in e-commerce and a change in the customer’s requirements.

Younger generations are much more adept at using technology to find the goods they want to purchase. They are not as cash-rich as their parents and are more selective about what they spend their money on, which may be an experience rather than a physical purchase. Socialising is important to them and they do not use department stores to the same extent their parents once did.

This change in the customer’s profile has created a huge problem. Historically, high streets have evolved on a piecemeal basis over time, with existing buildings being individually repurposed and expanded and new buildings being added to meet the growing demand.

Never before have we had such large developments built in one go in our town centres, mainly in prime locations – centres that have costs millions to create and have a huge amount of embodied carbon. The dramatic change in the customer’s requirements means that these mammoth schemes are no longer fit for purpose, but modifying them is not going to be easy. These centres, having peaked in value around 2010, have subsequently been constantly declining assets, a fact that many owners are unwilling to face. However, we should not hide from today’s true asset values because this will only hinder the required change and progress.

Change will have to take place or these centres will become a drain on finances. Many owners may just pass the keys back to the banks, which, in effect, is only passing the buck and leaving it to those banks to address these problems. The owners should not assume they need to face these issues on their own, but should rather join forces with local authorities and other key stakeholders, working together to deliver the right design and funding solution.

Correcting fundamental mistakes

Finding solutions will not be easy. No one size fits all and each project will have to be bespoke. The first principle of sustainable design is to consider whether a refurbishment/repositioning is feasible but we shouldn’t shy away from the fact that a total demolition may have to be considered. However, there has to be rhyme and reason to the solution, based on the understanding of two key principles: understanding the holistic functionality of our town centres and providing what the customer requires.

For excellent town centre functionality, we have to consider the urban design principles that make a town work as a whole.. We can no longer have mammoth, gated private developments that are not accessible by the public at certain times of the day, mostly in the evenings, dominating the cores of our town

The planning mistakes of the past have to be corrected, starting with a review of the historical street patterns to assess what needs to be repaired to reconnect the surrounding districts. New linkages will need to be considered to further break down the monolithic blocks into urban forms of a scale that suit their localities. Re-establishing a network of streets and spaces on a scale that is authentic to the place is fundamental. It is around this new urban networks that we can masterplan the uses the customers require today.

What do customers require? They require convenience goods, authentic independent retail, brands, food and beverage options, leisure, community facilities, sport, curated and pop-up retail, co-working, medical centres, aged living, care homes, hotels, residential and more. Most importantly, they require an experience. Most of these are functions our towns used to provide, working together to create a proper community.

Customers don’t require numerous department stores, retail multiples and oversized shop units, underpinning the point that we need to reduce the quantum of retail space in our town centres without losing the active frontages. Converting this retail space to other uses requires careful consideration, ensuring the mix of uses work holistically with the town centre . It is important to recognise that conversion may not necessarily be an option, with a new-build approach being the only long-term solution in many cases.

Many of these shopping centres were covered malls over two or three levels, with parking above. Solutions to be investigated include the removal of glazed roofs to create open streets, with other uses replacing the upper level retail space. Reducing the size of retail units while still retaining their active frontages can leave void space to the rear, but this can instead be used for a variety of uses, from leisure boxes to home storage units.

Conversion of some of the car parking into such uses as residential, workplace, later living, care homes and leisure boxes is also possible, while redundant department stores may accommodate retail and F&B at ground level as well as residential, student accommodation, leisure, hotels, co-working spaces, medical centres and more on the upper levels.

Ultimately, total demolition may be the only solution, and we have previously taken this approach in such cities as Canterbury, Exeter, Bath and are currently proposing it in Bolton. Other current projects envisage the demolition of 30% of the existing retail space, the introduction of a new town square of high-quality public realm, a new cinema and restaurants in a redundant department store and a 30,000m2 later living and healthcare facility.

The reduction in retail space creates the required demand tension to support the letting and rental levels for the remaining retail space. However, this process will be financially challenging and we need to work closely with the local authorities and government bodies to help with funding.

Customers don’t require numerous department stores, retail multiples and oversized shop units, underpinning the point that we need to reduce the quantum of retail space in our town centres without losing the active frontages. Converting this retail space to other uses requires careful consideration, ensuring the mix of uses work holistically with the town centre . It is important to recognise that conversion may not necessarily be an option, with a new-build approach being the only long-term solution in many cases.

Many of these shopping centres were covered malls over two or three levels, with parking above. Solutions to be investigated include the removal of glazed roofs to create open streets, with other uses replacing the upper level retail space. Reducing the size of retail units while still retaining their active frontages can leave void space to the rear, but this can instead be used for a variety of uses, from leisure boxes to home storage units.

Conversion of some of the car parking into such uses as residential, workplace, later living, care homes and leisure boxes is also possible, while redundant department stores may accommodate retail and F&B at ground level as well as residential, student accommodation, leisure, hotels, co-working spaces, medical centres and more on the upper levels.

Ultimately, total demolition may be the only solution, and we have previously taken this approach in such cities as Canterbury, Exeter, Bath and are currently proposing it in Bolton. Other current projects envisage the demolition of 30% of the existing retail space, the introduction of a new town square of high-quality public realm, a new cinema and restaurants in a redundant department store and a 30,000m2 later living and healthcare facility.

The reduction in retail space creates the required demand tension to support the letting and rental levels for the remaining retail space. However, this process will be financially challenging and we need to work closely with the local authorities and government bodies to help with funding.

Rewriting the rules

The financial model on which these retail centres were previously appraised has to be completely rewritten. Values based on declining Zone A rents and yields are longer relevant. We need to understand the importance of sustainable rents, essentially meaning what can the retailers afford to pay, which should follow the low base rent and turnover formulas.

In reality, the only thing that really matters is how we maximise the income generated from the development through effective management – growing this on a year-by-year basis and demonstrating the development’s longevity. We must also not overlook the value of our public realm and the income, no matter how small, that can be generated from this through curation.

The art of town centre management has to be taken to the next level and will be akin to managing a resort or leisure park, taking lessons from the likes of Disney, which knows how to deliver an experience. Gone are the days when a shopping centre owner could let a retail unit on a 25-year lease, walk away and just collect the rent. Now is the time for true collaboration between the owners and the operators, both sharing in the success.

Achieving the right solution will be a challenge, but we can no longer paper over the cracks. We have to grab the opportunity and produce a form of development that is adaptable, responding quickly and inexpensively to future market forces, maintaining their relevance and ultimately standing the test of time, something their forbears failed to do.