Repurposing the department store

Repurposing the department store

Department stores, once the cornerstone of any successful high street or shopping centre, are being closed down at an unprecedented rate, with some well-known names disappearing altogether. Owners and asset managers, faced with the possibility of a sizeable bank of empty space, are having to explore potential alternative uses for former department stores – many of which are not easy to repurpose or are too architecturally valuable to demolish. In this Insight paper, Daniel Morgans, using data and analysis from CACI Property Consulting Group, examines the reasons for the format’s decline in fortunes and explores potential ideas and options for decision makers for the repurposing of former department store space.

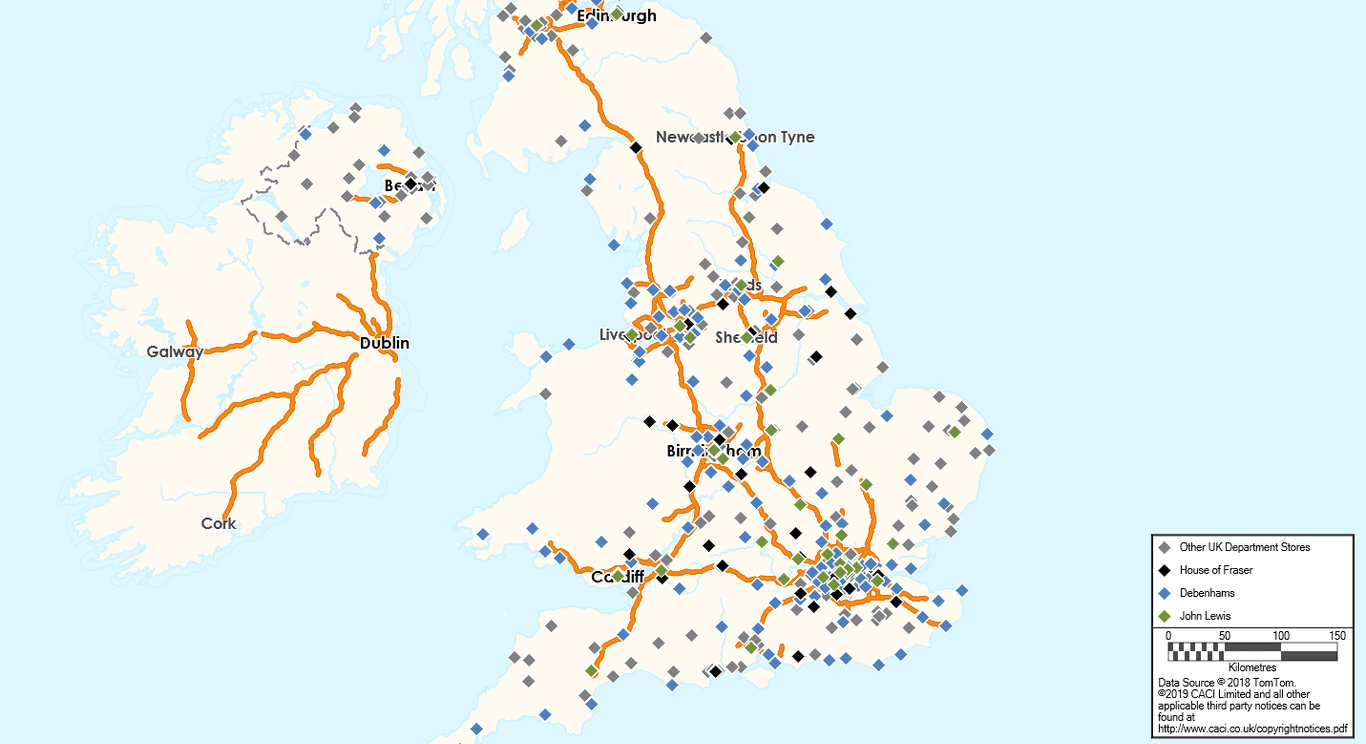

UK department stores. Source: CACI, Retail Footprint

The boom era

The department store is a retail establishment which offers a diverse range of goods within the same building, with the range divided into easily understood sections – departments – creating a coherent layout for ease of customer navigation. Offering a diverse range of goods, from perfumes to televisions and children’s toys to jewellery, they often epitomised, for many people, the height of luxury and the best standards of service.

The concept spread to major cities throughout the UK and Europe during the 19th century. Famous names, such as Harrods, Whiteleys and Liberty in London, Au Bon Marché and Galeries Lafayette in Paris and Macy’s in New York, were all founded in the 1800s. Many of these stores evolved from smaller buildings on site to become the large-scale establishments known today.

Selfridges, established in 1909 on Oxford Street in London, was the first to use extensive advertising and to market shopping as something to do for fun – using entertainment, exhibitions, relaxation areas, libraries and restaurants to encourage what we now call ‘dwell’.

As the 20th century progressed, the department store gradually became accessible to more and more people – by the latter half of the century, high street department store chains such as Debenhams, Littlewoods and John Lewis welcomed people from all classes and backgrounds. The format became a staple for every urban retail development – shopping centres relied on department stores as anchor tenants which would draw a significant cross-section of the public, and high-quality smaller retail units, to their schemes.

This reliability, which brought high footfall and vibrancy to our high streets and shopping centres for so long, is now a thing of the past, and the department store format is facing an existential threat.

Decline and disappearance

The once-formidable department store phenomenon is now in serious trouble, with dire predictions of its complete disappearance from our towns and cities. House of Fraser nearly collapsed in August 2018, before being bought by Sports Direct owner Mike Ashley. Year-on-year pre-tax profits at John Lewis dropped by 99% in the first half of 2018, while Debenhams’ share price plunged from 96p to 3p between 2015 and early 2019, before it entered pre-pack administration in April 2019. BHS disappeared completely in 2016, along with its pension fund and 11,000 jobs.

Why is this happening? There are several reasons:

- The online challenge – people no longer have the incentive to visit department stores that they once had, because they can find a wide array of goods at the touch of a button without leaving home, and often at a cheaper price.

- Rising overheads – the cost of maintaining a physical presence in the most expensive urban areas puts department stores at a further competitive disadvantage compared to online retailers.

- Unscrupulous owners – the BHS scandal illustrated a culture of corporate greed where making a short-term killing was put ahead of the long-term good of the business.

- Tired environments – lack of investment many department stores retain the look and feel they had 30 or 40 years ago, and are often difficult to navigate. Downsizing is required for many, but they are often on long leases of between 30 and 50 years.

- Tired offers – fashions change quickly, but department stores have not proved adept at keeping up – which is a particular problem for those which rely heavily on fashion-influenced merchandise

What is the way forward?

Although the department store format is currently facing its greatest challenge, it is not inevitable that department stores will disappear, and in many cases the answer will be to downsize the amount of retail space and find alternative uses for either the upper floors or a part of the building.

Luxury department stores such as Selfridges and Harrods are still thriving because they invest in the visitor experience. Others, such as John Lewis, are also looking to upgrade the visitor experience while putting much more emphasis on their online offers.

For example, John Lewis at White City recently won Retail Week’s 2019 ‘Best New Store’ award for its ‘department store of the future’. The store offers services such as home design advice, travel advice and personalised fashion consultations. Selfridges is providing customers with more than just retail, with connected experiences such as a denim studio featuring local designers and six themed campaigns per year. Thoughtful leadership and investment for the long term can help to guide department stores through this difficult time.

However, we can expect to see more and more department stores closing in the coming years. That then raises the question of what can be done with the spaces they have inhabited – many of which are landmark buildings at prominent urban locations.

In many cases, demolition will be necessary because their layouts and structures will not lend well to repurposing – especially for putting to other retail-based uses. However, several department stores sit within listed buildings, or form an important part of the surrounding built environment, so demolition is not an option. Other department store spaces will be more easily repurposed. An exciting example of a repurposed department store in a prominent location is Whiteleys in Bayswater, which is set to include a mixed-use development of hotel, residential and retail in a once tired and failing building.

Careful thought is thus necessary about how to adapt and reuse these spaces in a way which will ensure that the buildings thrive for decades to come, continuing to play an important social and economic role in their areas and to make positive contributions to the urban fabric.

There are a number of possible strategies for saving and repurposing former department store buildings, some of which we look at below.

Hospitality

The hospitality market is constantly changing, and brands such as Generator and Moxy make a great success of taking difficult city structures and providing an authentic and bespoke experience for young travellers. Modern tourists seek buildings with a visible connection to the city they are visiting, in an accessible location close to the best bars and restaurants. We are hopefully seeing the demise of homogenous brand roll-outs that look the same no matter in which country they sit. Therefore, 19th century department store structures in European cities lend themselves well to creating this authentic atmosphere, and, with a city centre location, the ingredients for a successful city-break hotel or ‘flash-packer’ hostel are there.

Hospitality – Constraints

Whether the hospitality offer is a youth hostel, a 3-Star business hotel or a luxury boutique, the ingredients are likely to be very similar. Hotels need active ground floor spaces and a generous lobby with direct access to lifts, along with associated restaurant and bar zones facing the street. These need to be placed at the front of the hotel, with direct access to back-of-house corridors that do not cross the public spaces. The back-of-house areas (perhaps 20% of the total floor area) may consist of a laundry, kitchens, offices, staff lockers and amenity space, and require rear access to a service yard with a certain amount of parking for staff vehicles. Basement spaces can be useful for back-of-house provision, but it is necessary to be mindful of rules on providing daylight for working spaces, should offices or kitchens be placed underground – gyms and swimming pools could potentially be placed there instead.

Guest room sizes can vary from 18m2 for lower-end brands to 40-50m2 for the larger rooms and suites in a luxury offer. Therefore, there is no single answer for module widths, as these can vary from the length of a bed (2-2.5m) to a more reasonable 4-4.5m in 3 or 4-Star brands. The natural rhythm of the existing windows and the structural grid will have a direct influence on what would be feasible, should the façade and structure need to be retained. Each room (hostels aside) will also need to be twinned with an adjacent room to share a riser serving the ventilation and plumbing requirements. Should the module widths work with the façade, the depth is likely to be 4-5m, with a 1.8m corridor, so the floorplan will need to contain an atrium or large lightwell to provide inner rooms with access to daylight. It is possible, with lower-end brands, to provide a number of rooms with no windows at all, but the default position should be to assume daylight is required in all rooms.

Below is a generic study of the potential conversion of half of a department store into hospitality use, which illustrates some of the points mentioned above:

Chelsea Market, Chelsea, NY:

A curated collection of artisan stalls, cafés, bars and restaurants over one million square feet of ground floor space, with a young, urban and industrial aesthetic.

Union Market, Washington DC

A mixed development including a market hall, where young experimental street-food brands are mentored and developed to create viable businesses.

Roman and Williams Guild, NY:

An interesting mix containing a florist, a library, a furniture shop and a high-end restaurant in a single space. This example is only 7,000 square feet, but the concept could easily be extended to something much larger.

Other uses:

Hospitality

The hospitality market is constantly changing, and brands such as Generator and Moxy make a great success of taking difficult city structures and providing an authentic and bespoke experience for young travellers. Modern tourists seek buildings with a visible connection to the city they are visiting, in an accessible location close to the best bars and restaurants.

We are hopefully seeing the demise of homogenous brand roll-outs that look the same no matter in which country they sit. Therefore, 19th century department store structures in European cities lend themselves well to creating this authentic atmosphere, and, with a city centre location, the ingredients for a successful city-break hotel or ‘flash-packer’ hostel are there.

There are possible constraints to be borne in mind when considering a conversion to hospitality use:

- The scheme would require an active ground floor façade – more than for an equivalent residential or office conversion

- It would also require a generous lobby with direct access to lifts and food & beverage, although this can be on the upper floors

- Back-of-house spaces may constitute up to 20% of ground floor and basement space

- The natural structural rhythm of the windows and grid

- Guest room sizes can vary from 18m2 for lower-end brands to 40-50m2 for the larger rooms and suites in a luxury offer

- Module widths can vary from the length of a bed (2-2.5m) to a more reasonable 4-4.5m in 3 or 4-Star brands Each room (hostels aside) will also need to be twinned with an adjacent room to share a riser serving the ventilation and plumbing requirements.

- Should the module widths work with the façade, the depth is likely to be 4-5m, with a 1.8m corridor, so the floorplan will need to contain an atrium or large lightwell to provide inner rooms with access to daylight. It is possible, with lower-end brands, to provide rooms with no windows at all.

Below is a generic study of the potential conversion of half of a department store (central split) into hospitality use, which illustrates some of the points mentioned above:

This example (below) in northern Europe shows a triangular-shaped existing department store repurposed for hotel use. The convenience of having no blocked sides means that all of the perimeter rooms can access natural light, but as the depth of the store is so great, the only way to employ the floor space with additional internal rooms is to insert an atrium into the centre. This would be an awkward proposition for residential as the overlooking distances would be too small, but mitigation factors such as sandblasted glass can be used for hotel rooms.

Residential

The decline of the department store format coincides with a crisis-level shortage of residential space in the UK, particularly in the South-East. Given that department stores, taken together, occupy a massive bank of urban space, it would seem obvious that former department stores, whether demolished or redeveloped, provide one potential solution to the residential shortage – after all, much of the infrastructure, including transport services, water, electricity and gas would already be available.

Repurposing department store sites for residential use would provide attractive places to live for younger people who prefer the dynamism of a town or city centre. This would help to bring life to those urban centres, particularly in the evenings – providing the basis for an economic renewal.

The potential challenges are very similar to those explained in the hospitality analysis:

- In many planning policy statements, single-aspect dwellings are discouraged, particularly in north-facing façades.

- Typically, single-aspect apartments should be a maximum of 7m-deep, and dual-aspect 10-11m. Therefore, an atrium is a likely solution, with rear bedrooms or kitchen spaces facing into the centre.

- Residential amenity space is normally required by planning authorities

- Some visitor or disabled parking is required, even in city centre schemes, where 0.2 to 0 cars per apartment may be allowed.

Below is a generic study of the potential conversion of half of a department store into residential use, which illustrates some of the points mentioned above:

Filene’s, Boston:

An example of a successful office transplantation is the former Filene’s Department store on Boston’s Downtown Crossing. Filene’s opened in 1912, occupying a whole block by 1929. The Beaux Arts-style building, the last major project designed by the famous Chicago architect Daniel Burnham, was closed in 2006 following a merger with Macy’s (which had its own existing premises directly across the street).

The Boston Landmark Commission voted to place protection orders on the façades of the historic original buildings, now renamed the Burnham Building, but the interior was completely redeveloped and the top four floors now serve as office space for French advertising and PR company Havas and its subsidiary Arnold Worldwide (as well as retail space for Primark).

Havas wanted a space which combined a sense of history with an environment which encouraged innovation and creativity, and that created a ‘wow’ factor for the agency’s clients and employees. They created a fully open and collaborative floorspace, creating the feel of a village community. A massive skylight floods the large and open lobby area with natural light, while heritage features such as the original brickwork and ceiling have been incorporated, with radiators and bannisters being repurposed.

Havas reports that the new office space has changed its work culture for the better and has brought in new business for them. The repurposing of the building, which also houses a new Primark store and supermarket, along with the construction of a new mixed-use tower on the site, has helped to enliven the Downtown Crossing area of Boston and bring vibrancy to what had been becoming a run-down district.

Multi-leisure space

Any successful city or town centre regeneration project needs to include a mixture of different leisure activities. One way of doing this is to create a multi-tenancy leisure ‘box’ by adding uses such as bowling, VR, table tennis, a pool hall, indoor skydiving, trampolining, indoor climbing, wave riders, a KidZania indoor city and crazy golf, to name but a few.

Some of these will naturally require greater headroom than the normal dimensions of a department store, and so removal of floor slabs may be necessary. Key to the success of such a scheme would be a flexible floor plan, so that the varying size requirements of each tenant could be coordinated by a single management organisation.

Cinema

Another option is to demolish part or all of the internal former department store space, retaining only the façade, and to insert a cinema complex. The cinema industry is going from strength to strength at the moment, having reversed a decline in fortunes in the late 20th century. In 1985, UK cinema admissions were at an all-time low of 54 million; by 2010, UK admissions had grown to 170 million.

An example of how cinema can revive footfall and economic fortunes is Gloucester Quays. When the shopping centre began to suffer from reduced footfall, the developer’s team moved the cinema from a nearby building into the shopping centre. It was an immediate success, and now Gloucester Quays is a very busy retail development. The 14-screen Cineworld at Silverburn, Glasgow, increased shopping centre footfall by over 20% almost immediately upon opening in 2015.

The advance of digital technology means that less space is needed for cinema equipment, allowing auditoriums to be arranged in many different ways and to be built in more complex locations. This fact lends itself to the possible repurposing of old department store complexes, the sites for which may have challenging spatial characteristics, as cinema and F&B schemes.

Chapman Taylor is currently working on the partial redevelopment of a UK city centre department store, the operator of which wishes to downsize its operations to cover just a portion of the building. The brief is to repurpose the top floor for a four-screen boutique cinema and a leisure unit.

The restructuring will require the roof to be raised to deliver the minimum height requirements in the auditorium areas. An additional challenge is that construction is to be carried out in an operationally ‘live’ building while trying to minimise disruption to the existing tenant during the project. This will obviously not necessarily be a consideration in the cases of completely closed department stores.

The key, whether for a partial redevelopment or a complete internal demolition, is to create a sustainable and future-proofed leisure location which can easily adapt to further changes in market preferences, particularly given the cyclical history of cinema attendances.

Conclusion

Naturally, any proposal or idea will require testing against market demand and the feasibility of the design will need to be analysed. Nevertheless, the concept of the department store as a centre of gravity in any urban location means that there are many positives to the repurposing of these grand and elegant structures – meaning that these buildings can continue to act as social and economic focal points for towns and cities for decades to come.

One of Chapman Taylor’s key strengths is the expertise we have in identifying how to add value to existing developments with well-considered design. We have worked with countless clients to renew, reconstruct, extend and reinvent developments of all types and sizes, helping to economically boost what were often tired or out-dated environments around the world. Clients come back to us repeatedly for our asset enhancement services because they know that we can spot economic opportunities in even the most challenging projects.