Reimagining retail parks: How to future proof and renovate existing assets

Reimagining retail parks: How to future proof and renovate existing assets

The current context

The UK’s retail park portfolio is still a major part of overall UK retail floorspace, and new developments such as Axiom, and Serpentine Green show that this format isn’t necessarily slowing down. However, existing assets are either suffering the churn of failing retail and F&B brands, reacting slowly to changes in consumer shopping habits or simply looking tired, ugly and out-of-date.

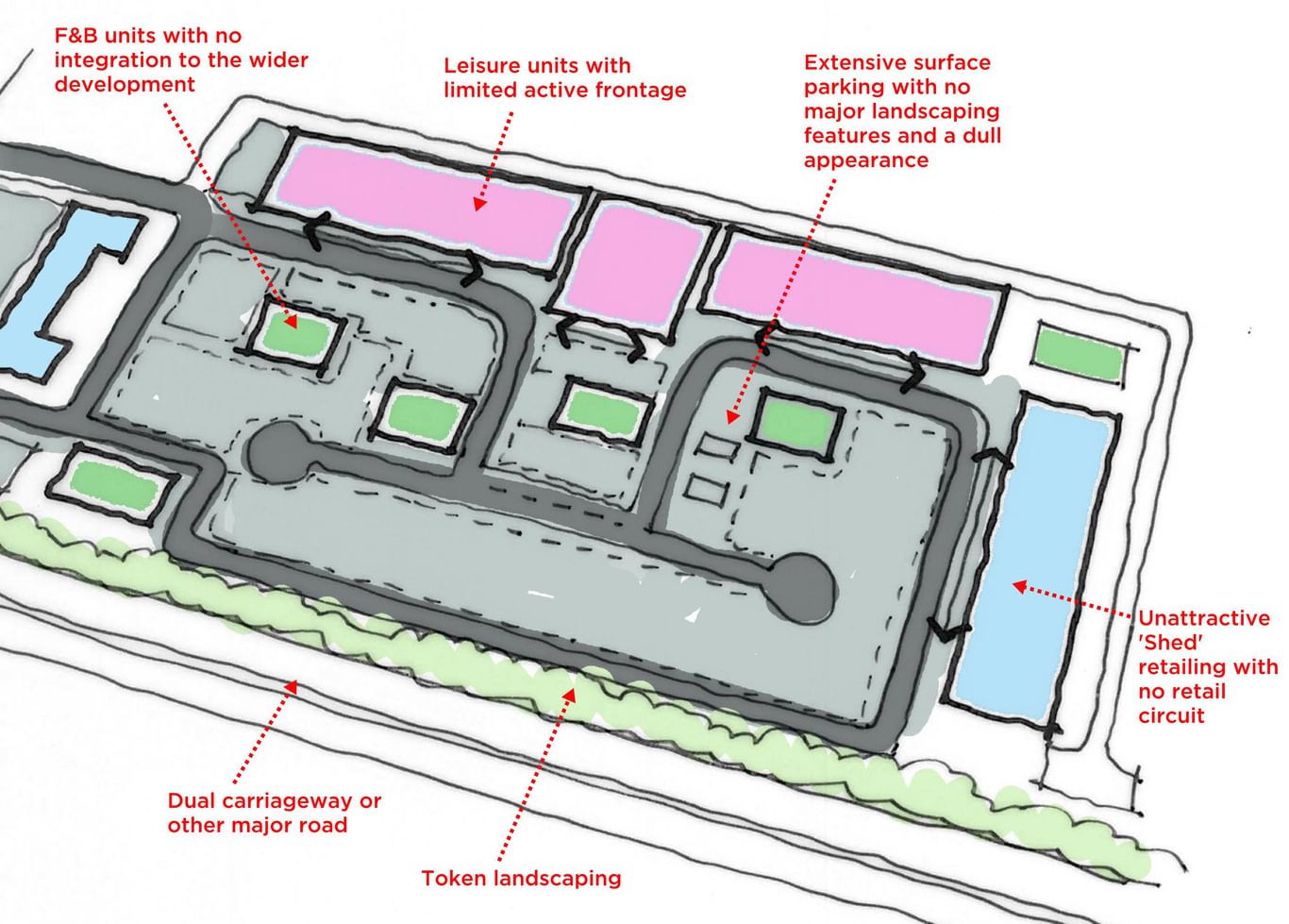

The typical retail park layout, created in the late 1980s and 90s, is broadly as follows:

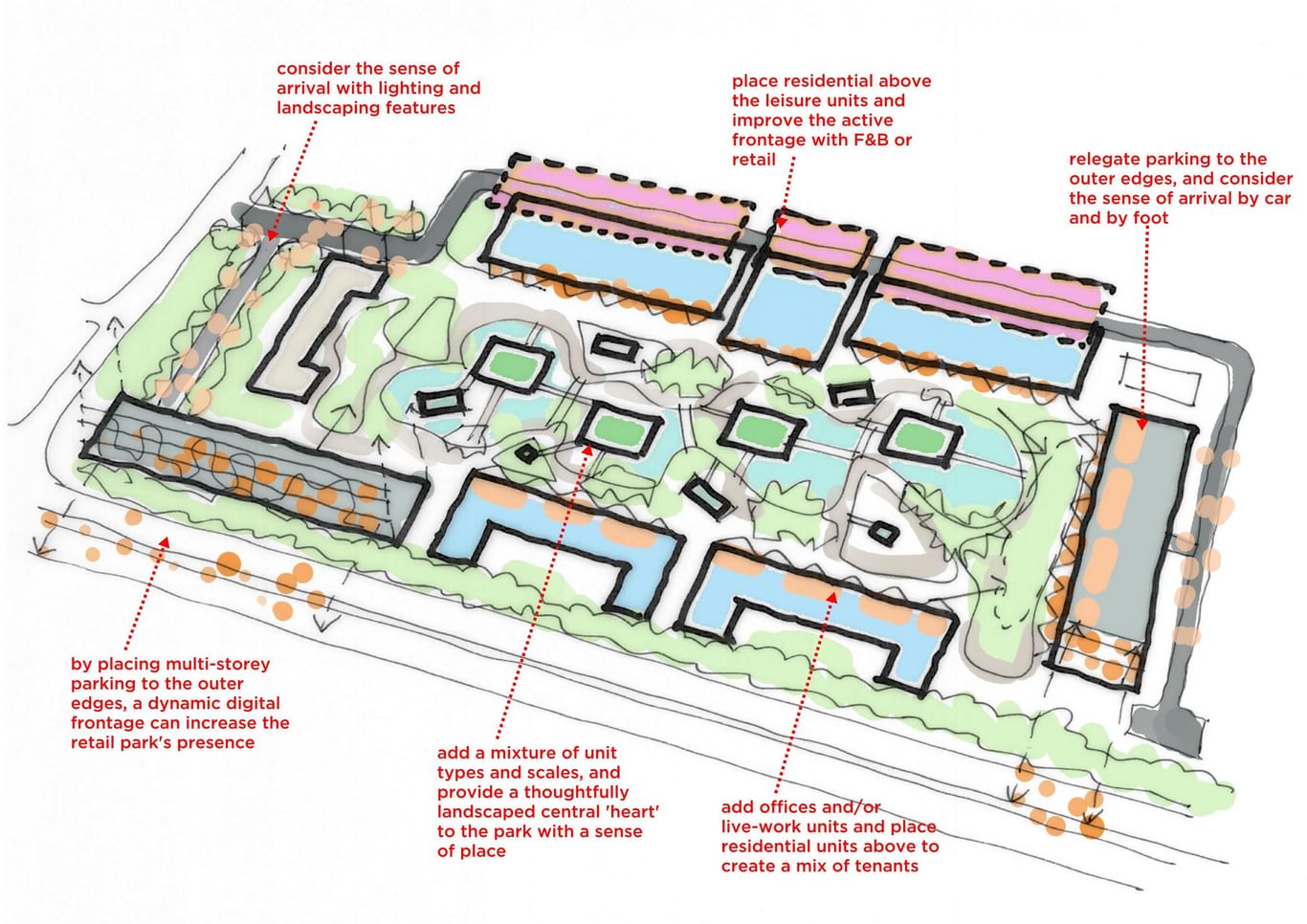

Image – a fictional existing example of a tired retail park

Arrive (and there’s problem number one) to the majority of UK retail parks or strip malls’ and you will find that ‘customer experience’ is pretty low on the agenda. Convenient parking, visibility of units, value engineering and accessibility from the highway are given priority. What results is, let’s face it, a series of aluminium sheds in a car park. This might be useful for buying impulsive or bulky items such as DIY, white goods or car equipment, but, in such a fast-changing retail landscape, that alone will not keep retail parks commercially sustainable – apart from in niche ‘industrial’ sites where the design aesthetic and the nature of the products is entirely appropriate.

It’s difficult to see the future of a ‘tired’ retail park if customer experience is neglected. If the proposition is for fast retail such as fashion, small electronics and supermarkets, then the competition is overwhelming. Most of these items can be bought online or in attractive mixed-use centres such as Westfield or Bluewater, where there is a curated experience and a constantly changing entertainment programme. So, the retail park has to work twice as hard to keep up. There are some shining examples, of course – Bicester Village illustrates that, if you relegate cars to the outskirts and create a warm, engaging street environment and a curated customer experience, you can create a successful formula. If the only positive thing you can say about a retail park is that it’s ‘convenient’, then it is going to become irrelevant pretty quickly. As they say, if you dislike change, you’re going to dislike irrelevance even less.

In the US, where our future is often predicted 10 years beforehand, the massive shift in retail habits has impacted upon ‘big box retail’ quite profoundly. Images of crumbling stores are a sad sight, but one team in Texas has turned a vacated Walmart into the largest single-storey public library in the US. Others have been turned into indoor raceways, gyms, hair salons and other, smaller divisions. The most interesting solutions, however, are to use the retail park as an opportunity for an integrated micro-community of housing, dining and retail.

This isn’t to suggest, of course, that current retail parks following the old formula cannot be successful; many things can create success, such as proximity (or lack thereof) to other facilities or the success of the shops themselves (discount supermarkets, cinema sites, a lack of equivalent F&B, etc.). However, it’s the evolving competition that creates the risk, either in the form of online retail or better, more engaging centres.

The customer base

The seismic shifts in technology and society, such as the internet and social media, and advances in personal transport, don’t need to be recounted here, and the ‘millennial’ is a much-stereotyped animal. Of course, retail habits have changed, and the cycle of awareness-confirmation-purchase-return is different to the purchase pattern of 20 years ago, but the process of visiting somewhere with friends to hang out, look at clothes and be entertained has not. Certain fundamental things haven’t changed and, certainly if you look at the country as a whole, most young adults don’t fit the entitled, entrepreneurial, fixie-bike-riding image that the media likes to portray. It may be a true image of a narrow metropolitan elite, but in most of the provincial and rural UK, the car is still king, and young adult lifestyles have changed comparatively less.

Therefore it’s worth just focusing on the simple things first; the fundamentals which will never change. People like to be entertained in an environment they enjoy, in the company of people with whom they identify. People also tend to like something only when they see it, and will not ask for something that they cannot imagine existing (Henry Ford – “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said ‘faster horses’.”). Therefore, if the competition manages to nail it, then the loser will be the one that has been complacent and hasn’t innovated. People will put up with rubbish only until something better comes along.

The retail landscape

Despite the fact that human interaction and the fundamentals of the customer base haven’t changed that much, the small shift (from a human perspective) in retail habits towards social media and internet shopping is having a seismic effect on the retail landscape. Retailers must now have a strong brand with a clear, unambiguous message, and must treat their customers as an ‘audience’ instead of as merely being ‘consumers’ of their product. The brand, and how that is experienced, is at the core of any potential success.

To succeed and be the winner in the race to avoid irrelevance, retail parks need to offer some fundamental concepts:

- A sense of arrival, and evidence of a ‘story’

- A curated guest experience, with seamless digital integration and an ever-changing programme of local events

- A sense of place and community, and an engaging, attractive environment

- Points of convergence and grandeur, and a mix of scales

- A mix of uses (leisure, retail, F&B) and a mix of tenancies that constantly evolves

- High standards and discipline, but not exclusive of a sense of fun.

- If appropriate, a residential, office and/or live/work component to the site.

- Prepare for the future, but don’t try and predict it.

The solution:

A sense of arrival

We have to acknowledge that, for most retail parks, economy and efficiency is fundamental. Nevertheless, those are not excuses for neglecting your audience. To compete, a retail park needs, with a low budget, to create a sense of fun, wonder and excitement for everyone from the moment they come within virtual or visual range. There needs to be a story.

Car parks need to be relegated to second place, tucked behind or away from the core retail environment. The journey, from the website and Google Maps through to the external signage and design and the design of the carpark itself, needs a strong sense of design flair. If the sense of arrival cannot be created while in the car, with beautiful landscaping, signage and visual impact, then it certainly needs to be present for the pedestrian thereafter. Design can help: interesting lighting design, a coherent and branded colour scheme, façade design that also follows the branded identity, sound and music and a human presence. None of this needs to cost huge amounts of money. It just needs to be fun and well-thought-through.

A curated guest experience, with seamless digital integration and an ever-changing programme of local events

The ‘story’ needs to continue after the arrival. Assuming that the arrival experience includes a branded website, branded icons on digital maps and a strong social media presence, digital integration needs to continue as the audience moves through the park. This could include updates on new products, a programme of entertainment events, talks, demonstrations, charity fundraising, street-food stalls and opportunities for local small business start-ups. The intent is to create a presence beyond the physical confines of the site.

This all requires curating (and no small amount of imagination and flair), and centre managers need to be part entertainment coordinators, part managers to make this work. However, it must also be recognised that the centre’s management, and the developer of the site, can only do so much – the rest is up to the tenants themselves. Retail brands have to recognise that they have an audience, not just a stream of consumers, no matter how humble or uninteresting they might think they are.

A sense of place and community, and an engaging, attractive environment

The diagram shown earlier in this paper has never been replicated in a successful historic town, village or market square. It has specifically arisen to cater for car arrival, and nothing else. Retail parks in environments such as these are doomed to failure, as the only binding force is a demand for convenience, which, as we have seen, is not enough on its own and has overwhelming competition.

Any retail park worth visiting needs to be master planned using the fundamentals of ‘place’. An esoteric word, it can mean many different things, but essentially there has to be a local identity and a feeling that the construction materials combine to form a sum greater than its parts. It’s very easy to say that six aluminium sheds next to a car park do not create a sense of place. However, trying to create a sense of place on a tight budget, on a confined site, demands immense skill and experience from the design team and requires a visionary client.

Points of convergence and grandeur, and a mix of scales

To compete in the challenging retail environment of today, retail parks have to create an experience. Customers will not hang around if there is nothing to hold their attention beyond the immediate purposes for which they came. Large shopping centres and retail-led schemes now routinely offer leisure and event space in which exhibitions, concerts, shows and other forms of entertainment – retail parks need to create central landscaped zones for this purpose too.

The retail park does not need to be architecturally dull. By incorporating a variety of spaces, differing in size, nature and purpose, designers can create a visually stimulating environment for visitors which draws them in and offers a reason to stay. Sensible, well-considered layouts can create interesting, even dramatic, meeting point areas where visitors can dwell.

A mix of uses (leisure, retail, F&B) and a mix of tenancies that constantly evolves

The enclosed, retail-only model for shopping centres and retail parks is fast-becoming a thing of the past. As part of the creation of a sense of experience, leisure and F&B components are becoming increasingly important as a means of attracting customers and encouraging them to stay for a substantially longer period of time.

Retail parks will only survive in the long term if friends, couples and families can be enticed to stay for a few hours rather than just a few minutes, and providing more than one reason to visit will be fundamental to that. Cutting and carving leisure and F&B into existing retail parks will substantially increase dwell-time, which will help to ensure the economic health of such schemes.

High standards and discipline, but not exclusive of a sense of fun.

Nothing signifies the economic decline of a development as much as a deterioration in its appearance and standards. To ensure that the retail park thrives in the long term, it is vital that the very highest standards are maintained in terms of cleanliness and politeness, particularly through excellent staff training and regular, timely maintenance.

It is a well-worn cliché, but it remains true that the customer must come first – at least in terms of ensuring that they are offered the respect of a well-run and mannerly service. However, this strict standard is not mutually exclusive of allowing for a sense of fun and quirkiness – rather, the two can and should enhance each other.

If appropriate, a residential, office and/or live/work component to the site

There is a chronic shortage of housing in the UK, with an urgent need for hundreds of thousands more residential units, particularly in the south-east. Retail parks offer a great opportunity to help ameliorate this crisis, as well as to provide ideal locations for office spaces of varying types – they have the space, the infrastructure and, usually, the requisite zoning and planning permissions.

The incorporation of residential and office provision into retail parks offers the opportunity to create a sense of community, turning the retail park into a hub for residents and workers, as well as for shoppers. One design option is to place those uses above the retail units, creating a mixed-use ‘village’. This could help achieve a critical mass in terms of population at any one time of day, opening up the possibility of a night-time economy for the retail, leisure and F&B components of the scheme.

Prepare for the future, but don’t try and predict it

Much is spoken about future digital advances in point of sale augmented reality and social media networks, and how internet shopping can work alongside physical stores. But these are unlikely to affect much more than the digital infrastructure around a development, and the interior design of units.

More fundamental shifts might come from personal transport technology, delivery methods (such as flying or vehicular drones) and the strategy for delivery warehousing. Whereas it is important to create flexible environments to potentially cater for such eventualities, it is important that developers don’t try and predict the future. An investment in user experience may even mitigate such advances, as customers (or ‘audiences’) choose to have human experiences rather than sit at home and wait for their packages to arrive. One only has to look at the rise and relative fall of e-readers to realise that technology can only take us so far. Human experiences, such as tactility, social interaction, excitement and adventure will always prevail, and will sit alongside technological advances rather than be overtaken by them.

Conclusion

Retail parks, like other areas of the retail sector, are having to rethink their business models and adapt very quickly to the extraordinary pace of transformation now taking place. Those which believe that doing little or nothing is an option will soon find themselves obsolete.

However, the changing retail scene offers an excellent opportunity to create something wonderful from what were often previously rather dull and utilitarian built environments. By embracing the addition of complementary uses on their sites, transforming the ‘story’ that customers encounter and creating a brand new community experience, retail park owners and operators could find themselves achieving hitherto unimagined value from their assets.

Chapman Taylor is an industry-leading expert in retail and mixed-use design. Our new-build design experience and existing asset enhancement skills can help owners and developers find and add value to any retail-led development.