Last Mile logistics: an essential consideration for planning.

Last Mile logistics: an essential consideration for planning.

Last Mile logistics, also sometimes referred to as ‘last touch’ or ‘last leg’, is a widely adopted term for the final journey of goods to the end customer. This last stage can be more than a mile but tends not to be in double digits. A ‘Last Mile facility’ is the building used at the start of that last stage. In this paper, Director Peter Farmer explains why changing demand is pulling these facilities closer to our urban and suburban residential environments, and the many implications for planning.

The rise in online shopping

COVID-19 has accelerated our penchant for internet shopping.

At the height of pandemic restrictions in April 2020 retail sales fell by a quarter compared with pre-COVID levels. Overall sales have now recovered this lost ground but in store sales are still nearly 10% down; online sales are still up by nearly half on the start of the year[i].

Whilst many stores have seen the proportion of online sales increase over the last couple of years, sales from online-only companies have remained relatively flat. This means the boost in online has been driven by a move from physical stores to their websites. In store food sales remain high, but there has also been a significant increase in online sales, accounting for nearly 10% of all sales.

Research by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development suggests that changes in online activities are likely to outlast the COVID-19 pandemic. The research covered Brazil, China, Germany, Italy, the Republic of Korea, Russian Federation, South Africa, Switzerland and Turkey and suggests that although transactions have increased, the average value of transactions has slightly dropped. This indicates increased interest in value for money. Coupled with this growth has come a sharpening of customer expectations in terms of service from online sites – quick and effective delivery has never been more important.

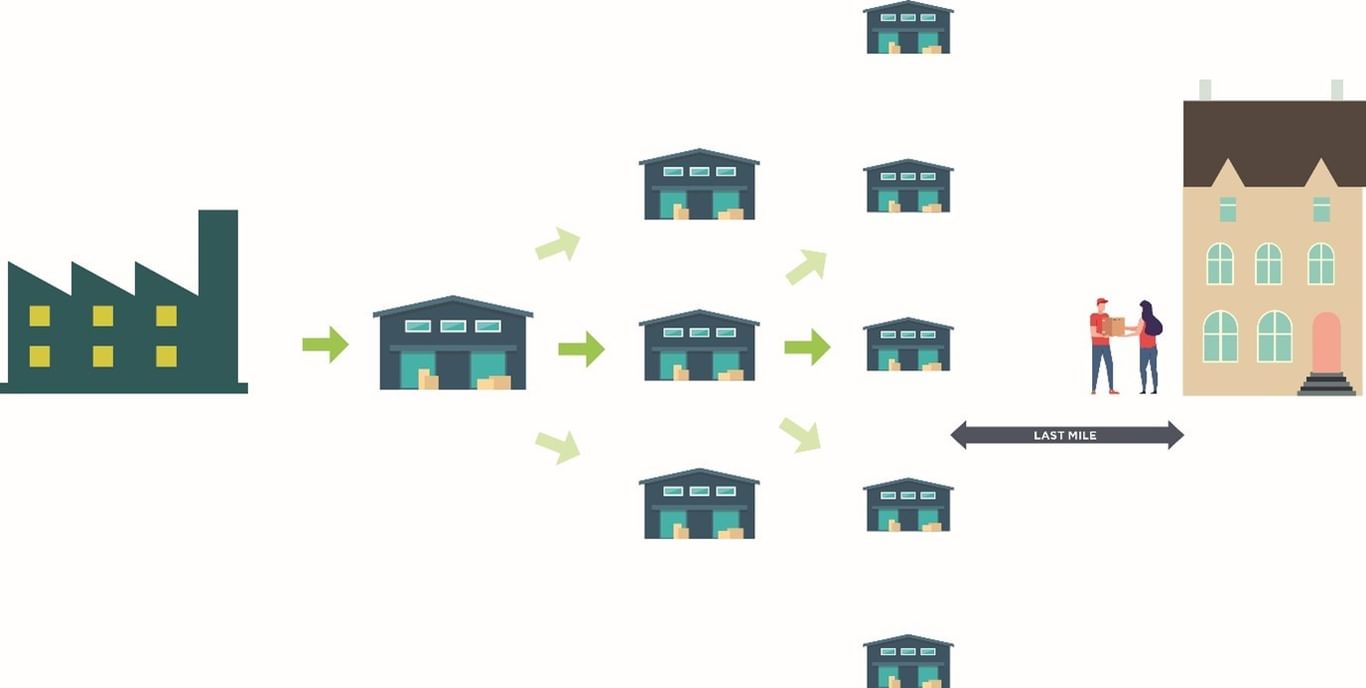

Last Mile facilities are becoming less remote

Efficiency of the fulfilment chain is a fundamental goal - keeping costs down and reducing the number of steps in the process. A reduction in fulfilment timing and improving service standards has become a given. This has led to significant growth in ‘Last Mile’ facilities. These facilities, integrated into towns and cities, provide the last staging post between the consolidated chain and the final customer. Previously, individual deliveries would be consolidated into a vehicle which would make several stops over a relatively large area from a more remote warehouse. ‘Last Mile’ facilities are now more likely to be made from a much closer warehouse and over a smaller area. This provides quicker and more reliable timings.

For the retailer and logistics company, this is also the most expensive step (as much as between 20-40% of the cost of the item and between 40 - 55% of the handling cost[ii]) due to the location of the unit and the lack of consolidation. For those of us working in the production and logistics sector, there is an understanding of the importance of these industries’ thin margins which influences the capital expenditure and operational expenditure of the buildings we design. We know that anything we can do to drive efficiencies and provide additional value will be welcomed.

Some retailers are starting to use in town ‘High Street’ as mini distribution hubs, whilst some shopping centre owners are seeing the opportunity to use void space.

There are some fundamental requirements and characteristics to consider before settling on the right solution for the Last Mile facility:

Operation

The main function of the Last Mile facility is to take consolidated loads for final distribution to the customer. It’s essential that goods can move rapidly through the facility. Deliveries tend to arrive in large, consolidated loads in large vehicles and then they need to be sorted to leave in smaller vehicles, even down to bicycles. The facility may also feed static pick-up points.

The use of these buildings has tended to follow a traditional mail type pattern, being used intensively for short periods aligned with the peaks of national distribution cycles. However, with increased customer demand this pattern is likely to be challenged to spread and infill the gaps between the peaks.

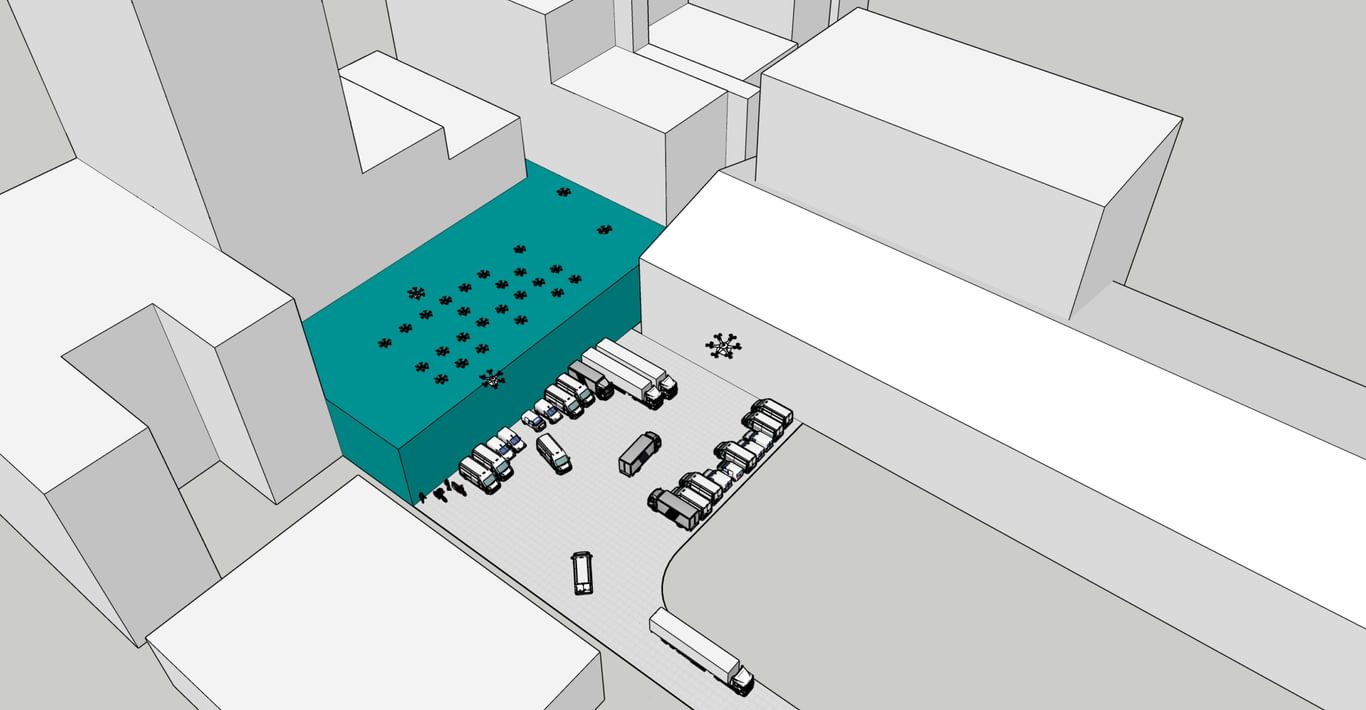

Most logistics companies are also now considering the use of automated vehicles and drones. Although still emerging, if a development is being considered now then automated vehicles could become a reality within its lifespan, so the impact should be considered. There is a view that large-scale commercial drones will soon carry parcels weighing less than 2.5kg up to 15 miles, easing road congestion and vehicle emissions and costs. In Australia, Wing, run by Google’s Alphabet, has been trialling drone deliveries of burritos, coffee and medication in a Canberra suburb since 2018, and launched a commercial air delivery business in the city last year[iii].

Drones are likely to have an impact on buildings – they will need areas to launch from and to be serviced. Automated vehicles will also need garaging and servicing. At the recipient end, a safe landing place will be needed which may slow adoption, particularly in the residential sector.

Access

When considering urban redevelopment, refurbishment or repurposing opportunities, access can be the most demanding element. As noted, consolidated loads tend to arrive in larger vehicles. This can be an issue in some locations however we have found that in most they can be accommodated. In locations where retail may be or have been the dominant use there is usually some delivery provision and accepted levels of movement. The real challenge is the distribution beyond, to the end customer, in particular the numbers of vehicles needing to be accommodated and the resultant movements.

A unit may well reach a peak in excess of 200 deliveries an hour - in other words 18 seconds each – so multiple bays and space are required. Inbound deliveries tend not to be the pinch point. Although not necessarily all will be articulated lorry size, or full, if the vehicles are large they can contain 16 - 32+ pallets with potentially a couple of thousand separate consignments. Offload times vary and are dependent on the lorry being tail gate or curtain sided. It’s not unreasonable to assume a 45 minute offload time so the provision of, say, two or three bays is reasonable. In very constrained but high-value locations operations may work with one bay but this gives no redundancy.

For distribution, if we were to assume it takes five minutes for a driver to park a small van, get a package and leave this would require 16 – 17 bays with no waiting or redundancy. It should however be noted that some deliveries may be grouped, or alternatively, be collected by cycle or another micro mode of transport.

Below, we consider the integration of the warehouse with other uses. In wider urban planning terms below ground distribution is being considered, much like the now mothballed London mail tunnels. This, combined with eVTOL drone distribution and larger inbound consolidated deliveries, could in the future remove most or all deliveries from ground level.

Mixed use

Location is important. Close to the end customer but also with good connections to regional and national networks.

The locations that we are looking at for these facilities have a much higher real estate value than to edge or out of town locations. So, we are developing schemes that look to intensify density and add mixed uses to support the overall business case.

Placing a distribution facility at a lower level presents several challenges. Ideally, this space needs to be as open, accessible and flexible as possible. Many of Chapman Taylor’s mixed use urban regeneration projects have successfully resolved the differing use requirements regarding access, means of escape, floor-to-floor and grid dimensions and the introduction of a lower-level warehouse is a step up in this. However, a warehouse at a lower level does present a potential fire load risk that needs to be carefully considered.

For practical reasons, the warehouse element is best suited to the ground floor. This is normally the default, with other uses such as residential or workplace above. In some locations, there is also potential ground floor value for other uses such as public realm commercial, retail and F&B. The warehouse needs little or no public front and therefore we tend to push this to the back and form some other uses at the front. In some cases, this can lead to looking to use more height, but moving items vertically is not ideal and becomes subject to handling equipment and the inherent issues this brings. There is therefore a careful value, cost and benefit balance to be struck.

We have considered putting the warehouse at the upper level but getting a larger delivery vehicle to an upper level takes a lot of space, which is valuable. It is also costly in respect of structure and can present safety issues. It is better to consider a split, keeping the large vehicles at ground level and the smaller ones at the upper level. This becomes more and more attractive as we start to integrate more micro-mobility and airborne distribution.

Given the rate of ‘disruptive change’ and emerging technology, we would always consider the future flexibility of the ‘Last Mile’ element of the development. Should distribution patterns change and the unit becomes redundant we don’t want to have an obsolete component to a mixed use development.

Specification

Unlike building a warehouse outside an urban area, designs and configurations are driven by location specifics and capacity needs.

The site needs good circulation and capacity. The building sizes (the warehouse element, excluding other mixed uses) tend to be between 3,000 – 5,000m2. Heights can be down to 8m clear, although we have considered lower for certain schemes where local constraints exist. The smaller building size vs external area requirement tends to lead to lower site densities which again puts pressure on use and land value in many urban locations.

Floor loadings will depend on the height of racking, noting that the purpose of these facilities is to distribute as quickly as possible - movement through the facilities is more important than storage. If footprint is constrained, the use of racking, mezzanines and handling equipment may need to be considered along with the degree of automation. If automated sorting is predominant this can be at a high-level freeing ground floor space.

Within the logistics sector, there is increasing interest in refurbishment and sustainability. At Chapman Taylor we have been placing our efforts in researching both areas as well as being involved in many projects where these aspects have been given a greater emphasis in the brief and design.

Over recent years we have tended to increase the amount of natural light in warehousing for wellbeing, safety and environmental reasons. As a warehouse below a mixed development will be challenged in this respect, we have started to investigate alternatives such as light wells through the other uses and side views/use of daylight.

Facilities

In the UK staff, driver and rider welfare have rightly become increasingly important. Staff attraction and retention have become more important as companies have rapidly expanded to meet demand. The need to attract new staff may ease in the future but there is equally an increased awareness and expectation of ‘wellness’ in the employment environment. Staff satisfaction is also key to the quality and efficiency of service.

With the emergence of AVs and drones we will see the need for garaging, servicing and in the case of the latter, launch and landing areas.

What are the wider implications for urban and building design?

Developments in the logistics sector will influence other areas of design. We will see more collection points appearing, like the older post box venues, within the public realm. All types of developments, including residential, may see the need for some form of delivery facility whether that is a multi-use collection point or a dedicated drone landing point.

The need for ‘Last Mile’ facilities has now become a key strategic planning issue and a component of required social infrastructure alongside other virtual services and utilities. Provision needs to be considered at local and national government level as land is considered for redevelopment, particularly for housing.

At Chapman Taylor, we’d love to talk to you about these challenges. Peter and his team are on hand and can be contacted by email: pfarmer@chapmantaylor.com

[I] Source: Office for National Statistics – Monthly Business Survey – Retail Sales Inquiry

[II] https://www.shdlogistics.com/l...

[III] https://www.savills.com/impact...