Vacant to Vibrant: Sustainable strategies for shopping centre transformation

The rapid evolution of retail in recent decades has had a profound impact on the built environment, particularly the once-thriving shopping centres that anchor many towns and cities across the UK. Born from a legacy of trade and community gathering, these large-scale developments played a vital economic and social role throughout the 20th century. However, the rise of e-commerce, shifting consumer habits, and the acceleration of online retail following the COVID-19 pandemic have left many shopping centres underutilised, struggling, or altogether obsolete. In this Insight paper, Architect Raluca Bratfalean-Igna explores the challenges and opportunities presented by this transformation, proposing sustainable and creative strategies to repurpose and revitalise these spaces. Through a careful analysis of architectural typologies, locational advantages, and reuse potential, it argues that shopping centres—once symbols of consumerism—can be reimagined as vibrant, multifunctional assets that support contemporary urban life.

Approved planning application for demolition of Debenhams store and construction of St David’s City Square in Cardiff.

Evolving retail landscape

Shopping centres are much more than just retail spaces. They are the heirs to the long-time legacy of trade as a backbone of any developing civilisation. Starting from an informal collection of stalls, colourful bazaars and bustling markets, those early shopping destinations were not only crucial for economic growth, they were also the places where communities gathered, socialised and entertained.

Since the 1960s, shopping centres have become an integral part of towns and cities across the UK, often playing a vital role as the leading shopping destination. Consequently, some previously popular high-street department stores have faced closure or have been relocated as anchor tenants in shopping centres.

With the majority of the shopping centres being built within cities and towns, this has led to the dramatic transformation of large areas that were formerly prime retail locations serving the wider community. In some cases, entire buildings, streets and neighbourhoods were eradicated to make way for these new shopping experiences.

In recent years, we have witnessed significant changes in customer preferences due to the rise of e-commerce, with online platforms increasing their sales percentage to 20% in 2019. COVID-19 further accelerated the online shopping trend, which currently accounts for 26% of retail sales in the UK.

The shift in customer behaviours has caused a decline in foot traffic to physical retail spaces, particularly shopping centres, which rely on anchor stores and high visitor numbers to sustain smaller retailers.

While not all shopping centres are suffering, with regionally dominant shopping centres still able to maintain high occupancy rates, many smaller centres have struggled to secure long-term tenants. According to the 2024 “Shopping Centre Revisited” report by Lambert Smith Hampton, 12% of shopping centres may require demolition and replacement with other functions, with a further 40% of retail spaces in need of repurposing.

This presents new and exciting opportunities for communities, councils, and investors to rethink the future of retail, while also improving and reinventing town centres across the UK.

Architectural anatomy of shopping centres

While each shopping centre is unique and responds to its own context, the majority of shopping centres in the UK follow similar design principles.

The sheer scale of shopping centres, intended to accommodate high footfall and large areas of commercial space, becomes a challenge when retail demand declines. The growing amount of empty or underutilised space can lead to urban decay and increased anti-social behaviour. The presence of vacant units also leads to depreciation in value, for the remaining tenants, the owners and even the local authorities due to a reduction in income from business rates.

Shopping centres are typically designed as enclosed environments with controlled artificial lighting within the retail units themselves. Typically, only the main mall spaces are provided with skylights offering the only source of natural lighting. While this principle has worked well for retailers that depend on carefully curated lighting conditions to present products in an attractive way, it also presents challenges for the majority of other potential uses, which benefit from access to natural lighting for their operation and for the well-being of their users.

Many city and town centre shopping centres were designed purely as an internalised retail environment, often leading to significant spans of blank and inactive street frontage. The absence of active windows and entrances not only limits the natural lighting inside the building but also visually and functionally disconnects the retail offer inside from its local context and passing trade.

Challenges

Unlocking opportunities

Despite all the challenges, town and city centre shopping centres are filled with potential.

A central location is usually considered one of their most significant assets. Originally positioned to attract maximum foot traffic, these underperforming shopping centres are already destined to be desirable for a wide range of potential alternative uses.

These central locations are usually supported by convenient transport links, providing accessibility by foot for local residents and all means of public, and also private, transport. The strong connectivity not only reduces the need for additional investment in transport infrastructure, but also encourages sustainable mobility solutions. The reconfiguration of an existing shopping centre asset represents a valuable opportunity to reinstate historic pedestrian routes and to create new ones, enhancing and improving permeability within the city centre.

While the large size of retail spaces is often seen as a challenge, it can also provide significant flexibility for future developments. These expansive plans can be reconfigured and redesigned to accommodate a mix of complementary programs under the same roof.

Being built to support high numbers of visitors, and heavy floor loads, means these shopping centres have durable structures, often with larger spans. These “strong bones” of the buildings make them highly suitable for adaptive reuse, reducing the need for complete demolition.

Opportunities

Strategic directions for the future

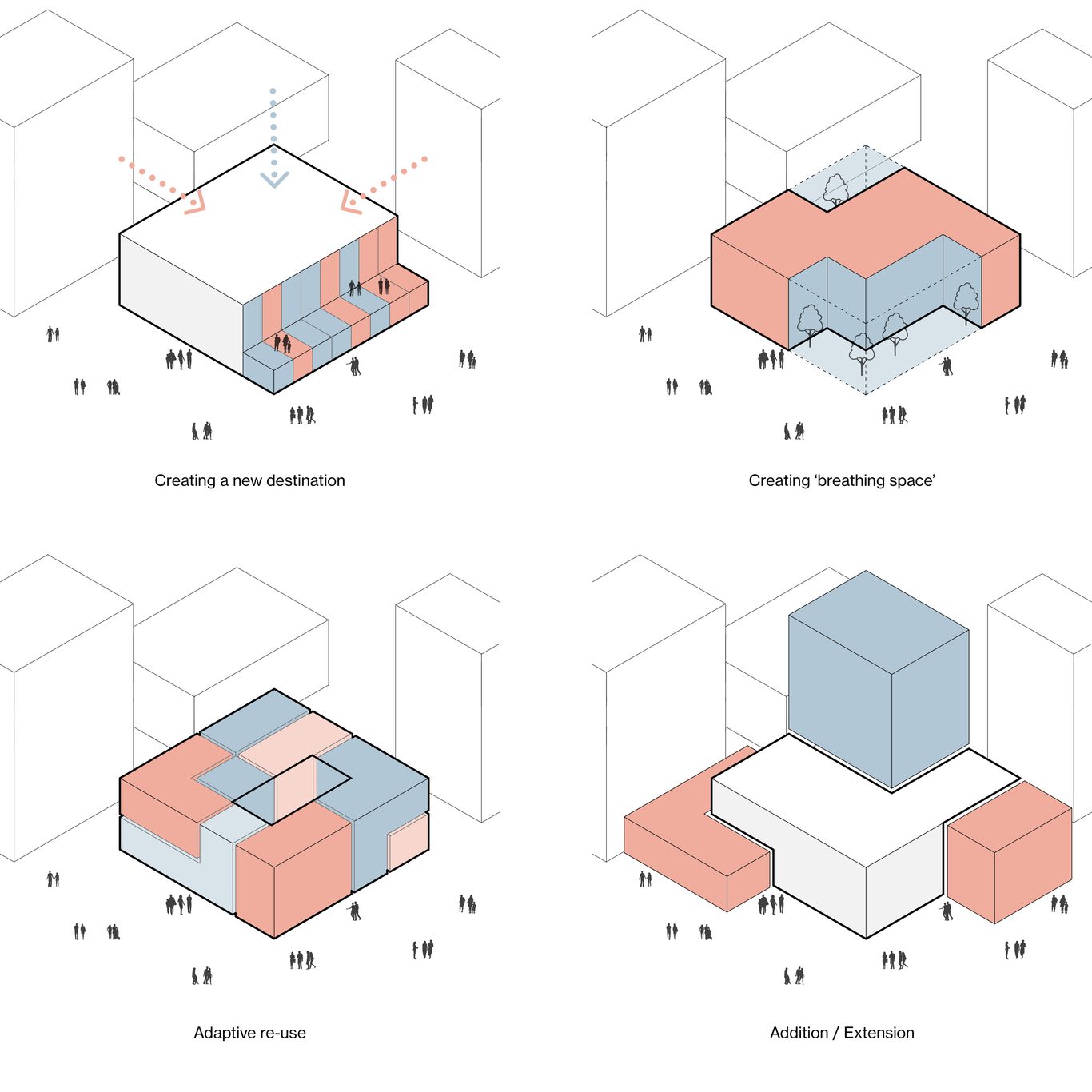

When analysing potentially stranded retail assets, it is important to take a holistic approach and to carefully consider local and emerging community needs, as well as understanding the environmental impact of the building. While demolition often seems like an extremely wasteful solution, it is sometimes an option we should not reject outright, especially when it offers the opportunity of creating new high-quality public spaces and introduce green areas to densely built areas. Nevertheless, before deciding on demolition, it is always worth considering other alternatives. Retaining the existing structure can help to reduce the environmental footprint of a redevelopment project by recognising the embodied carbon within the existing building fabric and also reducing the disruption, dust and noise that demolition can bring to the neighbourhood.

While retail is usually the largest component of the shopping centres, the decision to visit a shopping centre is often driven by other factors, including the quality of the F&B offer, entertainment options, or the availability of spaces to socialise. Incorporating leisure, cultural activities and hospitality can help transform underperforming retail assets into vibrant, multifaceted destinations.

The reduction of retail areas by eliminating poorly performing and low-value space can create opportunities for public squares and parks for relaxation and leisure activities. This “addition by subtraction” method brings increased value to the surrounding commercial assets by balancing the supply of retail spaces to meet a reduced demand, and at the same time making urban centres more attractive and visitable. An excellent example of this approach is currently being realised based on Chapman Taylor’s proposals for the City Square scheme in Cardiff.

The adaptive reuse of shopping centres offers the opportunity to transform underperforming retail assets into completely new functions, such as residential, workplace, cultural venues, community hubs, healthcare, or leisure destinations.

This radical re-assignment of the building’s functions should ideally target the retention of the existing structures, where possible. This can help reduce construction costs and environmental impact, while allowing the new functions to add significant social value to their communities.

Where the context and planning constraints allow these existing retail assets can also undergo more substantial interventions to accommodate additional programmes through vertical or horizontal extensions. The introduction of residential towers and office buildings can help transform an outdated shopping centre into a vibrant new mixed-use destination within the city centre.

Strategies

Solution to the stranded retail asset issue

The first step in addressing the issues surrounding stranded retail assets is to engage in a collaborative process involving all stakeholders; i.e. owners, developers, architects, local councils, neighbours and local communities. Understanding unique context-specific factors, local needs, and what drives customers decision-making, is an essential skill in developing viable options. This is also when good architects and designers can create the maximum added value for clients by looking at outdated shopping centres through the lens of hidden opportunities and coming up with the most creative solutions.

------

As shopping centres face an uncertain future, the path from vacancy to vibrancy depends on bold thinking, collaborative planning, and a commitment to sustainable transformation. While no one-size-fits-all solution exists, adaptive reuse, strategic redevelopment, and the introduction of mixed-use programmes present powerful alternatives to demolition. By unlocking the latent potential of these centrally located structures, we can help breathe new life into our towns and cities, creating inclusive, resilient, and future-ready urban environments. Ultimately, the success of these transformations lies in recognising the intrinsic value of existing assets and reimagining them not as relics of the past, but as catalysts for regeneration.