Designing for high-rise living

Designing for high-rise living

In this Insight paper, Director Michael Swiszczowski looks at some of the key factors to be borne in mind when designing high-rise living places.

The UK has seen a rapid increase in high-rise living, despite concerns about a Brexit-related slowdown affecting the residential market. It is estimated that London has 541 towers in the pipeline, 90% of which are residential¹. With pressure to accommodate a growing London population, tall buildings are being recognised as a crucial section of our housing mix. 68% of the towers in the London pipeline are located within the inner boroughs¹. However, given the promotion of opportunity areas*, tall buildings are also proving to be a deliverable in London’s outer zones. This is echoed in major cities outside of the capital; Birmingham, Liverpool and Manchester have also seen dramatic increases, both in the pipeline and in construction.

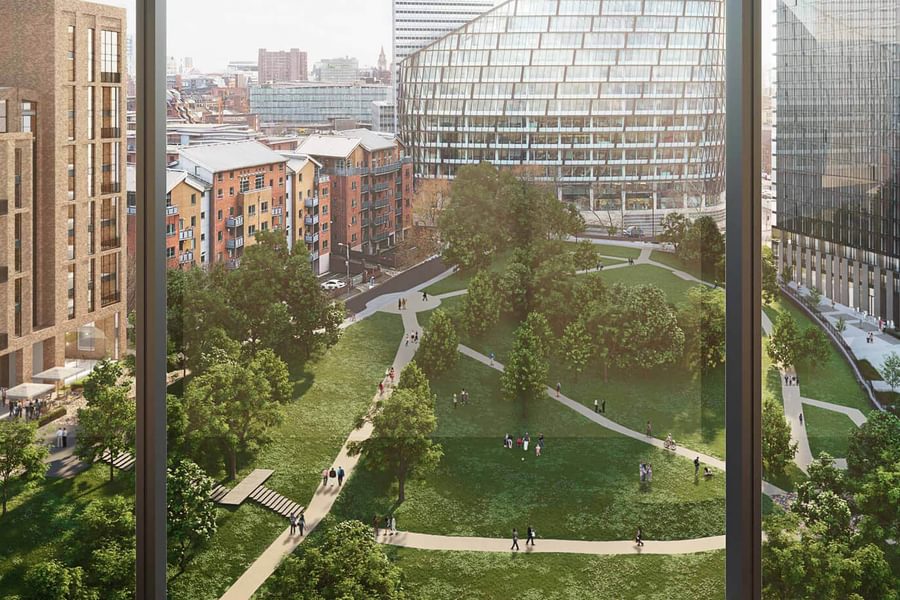

Chapman Taylor’s Manchester studio is currently designing a 26-storey Build-to-Rent (BtR) scheme in Salford, and construction has started on the 21-storey Meadowside development in Manchester. Meanwhile, construction has also begun on the much-anticipated Castle Park View residential development in Bristol, which will become a landmark on the skyline as the tallest building in the city when it completes in 2022. A 26-storey tower and a 10-storey building will book-end the main building, providing 375 apartments delivered in a mix of Build-to-Rent and affordable housing tenures.

Designing and constructing tall residential buildings such as Castle Park View presents particular challenges, not least that such landmarks attract greater scrutiny, but, when designed well, such developments can provide the basis for attractive and sustainable urban communities.

Architectural quality

Residential towers demand greater thought than many other typologies. Tall buildings affect a wide area and need to be carefully located and integrated, allowing their scale, form, mass, proportion and silhouette to have a positive relationship with adjacent buildings while allowing for the maintenance of existing views and framing key vistas.

Whether individually or as a group, towers can improve the architectural legibility of an area. For example, on the Liverpool Waters masterplan – one of Europe’s most important regeneration sites – Chapman Taylor strategically positioned towers in a cohesive group to emphasise points of civic and visual significance and to enhance the skyline of this World Heritage Site.

Tall buildings affect a wide area and need to be carefully located and integrated.

When designing tall urban buildings, it is important to consider the height in relation to nearby buildings and to integrate the buildings as extruded corners of the urban structure, rather than as standalone buildings.

The interface between the building, the ground and the public realm is key. It is fundamental that towers are integrated appropriately at street level to positively contribute to their surrounding context and to create a sense of place. To achieve this, solutions for access, servicing, parking and amenities need to be discreetly located to maximise active frontage. The uses and functions which are incorporated in the development need to complement those in the surrounding area, and should be planned to avoid doubling up.

High-quality public realm is also essential to accommodate pedestrian movement while allowing sufficient space for sunlight to penetrate and views to be appreciated. Careful analysis of the microclimate (such as overshadowing, light pollution, vehicle movements and wind modelling) is also required to allow pedestrians to enjoy the local environment.

The top of the building is also crucial – the building will be seen from far away and become a navigational tool for many people. The architectural design should be instantly recognisable and make a positive contribution to the urban skyline.

Opponents of high-rise developments often argue that they are not sustainable. It is true that, historically, towers have had a high embodied footprint, but this is changing. The world’s tallest timber building, the 18-storey MjØstårnet in Norway, was completed in March 2019. The main structural components of the building are composed of engineered timber, with glue-laminated timber used for beams and columns and cross-laminated timber used for the core walls. Wood stores carbon dioxide throughout its lifecycle, and the glulam production process requires little energy, so the tower has a very low carbon footprint. Researchers from Cambridge University’s Department of Architecture, through a combination of theoretical design and physical testing, have demonstrated the viability of timber buildings at much greater heights than has previously been possible, and have proposed the world’s first supertall (300m+) timber building.

Heating is the largest consumer of energy in our dwellings and, due to their compact form, towers are inherently thermally efficient. Creating a place for residents to live in a city also significantly reduces the impact of transportation. The 28-storey VArquitectos in Bilbao, which is the world’s tallest Passive House, and the Passive House students' residence at Cornell Tech in New York, which opened to residents in 2017, both prove that towers can be sustainable.

The economics of tower creation tends to promote a mono-tenure. However, achieving an appropriate mix is key to creating and maintaining long-term social sustainability. London’s Barbican, a post-war estate housing 4,000 people, is increasingly in demand as a place to live. It has three towers, two of which have 44 storeys while the other has 43. The Barbican’s success is partly due to the fact that the towers are set among low-rise buildings, and also that the complex includes a variety of community facilities, including gardens, children’s playgrounds and tennis courts. These attract a mix of part-time residents seeking a bolthole close to their offices, families and retired people.

It is more challenging to foster a sense of community in a tower – residents generally move straight from the lobby, via a lift, to their apartments. Many BtR operators actively encourage social interaction by employing friendly concierge staff, hiring community organisers, holding annual festivals and allowing pets. Providing communal facilities such as lounges, gyms and sky terraces, grouping mini-communities of similar apartment types and personalising circulation space can also reduce segregation.

Another big perception problem for high-rise towers is that they are considered dehumanising. However, this need not be the case if the human scale is reflected in the building façade. Towers need to work at two scales. In the distance, they need to offer a unified single form. Closer up, they need to allow for the expression of the individual home. The envelope should heighten a resident’s quality of life by maximising views, but should also provide a veil of privacy from the city. Incorporating ‘vertical greening’ such as the hanging gardens employed at One Central Park in Sydney, or winter gardens to replace balconies at the higher levels, are a good way of achieving this. It is also important to create visual connections to increase the perception of being part of a neighbourhood.

Recently, tall buildings in London have been the preserve of the super-rich. There is growing evidence that we may be on the cusp of a ‘paradigm shift’ to a rental-dominated market. This may end the criticism that residential towers are merely ‘safety boxes in the sky’, but brings with it a different set of challenges. Good management is critical to delivering secure, supportive and safe environments, and that needs to be factored into such schemes from the start.

The value of height

Whether a building is considered to be tall is relative to its surroundings. The definition of a tall building in the City of London is 150m (although City Hall counts those over 30m), but is generally accepted as being a building of 20 storeys or more. As a general rule, the higher the apartment, the greater the price premium. This not only reflects the enhanced view, but also the exclusivity of living towards the top of a tower. However, most tall buildings (62%)¹ in the London pipeline are between 20-29 storeys. This is due to a number of factors:

- The net-to-gross efficiency of a typical tower decreases with height. Core sizes inherently get larger as building height increases, and efficiencies are further diminished by the requirement for intermediate plant floors above 30 storeys.

Achieving an appropriate mix is key to creating and maintaining long-term social sustainability.

- Market economics – limiting the number of units coming to market can maintain sale prices. It is generally possible to do this on medium-rise developments, but is harder to achieve on towers.

- There are much higher costs associated with buildings over 30 storeys, due to their longer construction times. Taller towers can be massive engineering projects, constructed over many years, and therefore have a greater exposure to political, economic and social risk.

- Incorporating balconies above a certain height is not always recommended – the higher up the balconies are, the more uncomfortable the sensation for people using them. Alternative options include incorporating roof gardens and/or ground floor courtyard spaces. Using the roof in this way will impact the space needed for lifts and, therefore, the size of the core.

Maximising efficiency

Form, shape and technical complexity drive the cost of a tall building and are key factors in their viability:

- Wall-to-floor ratio – this reflects the quantity of facades so from a cost perspective, the lower the better. Projects in the Far East tend to score between 0.3 and 0.35, as they generally have larger more regular floorplates. In the UK, the ratio is usually higher due to the constraints of developing in a historic context. The impact of small irregular plots, combined with viewing corridor and rights of light, restricts floorplate size. Therefore, a range of 0.45-0.55 is to be expected.

- Storey height -a typical storey height is 3.0-3.2m, which allows a 2.5m floor to ceiling height in living areas.

- Slenderness – in very tall buildings, a high slenderness ration (the width of building in relation to its height) will typically increase costs, as slim towers require measures such as tuned mass dampers, to counter the high strengths of the wind in the vertical cantilever to avoid unwanted swinging. Structural engineers generally consider skyscrapers with a ratio above 1:10-1:12 to be slender.

- Floorplates should be maximised. The optimum size in the UK is 650-750m² (although this can be limited by the London Housing Standard requirement that each core should be accessible to generally no more than eight units on each floor). Depth should also be increased to mitigate the slenderness ratio, but this needs to be carefully balanced with the apartment layouts and daylight factors to avoid a detrimental impact upon quality of life and sales values.

- Core design – towers tend to have fewer apartments per floor therefore in order to improve the net-to-gross, the core needs to be efficient by optimising the lift and services distribution strategy and the structure following wind test results.

- The mix and size of apartments can significantly affect the floorplate. At lower levels, sales values tend to be greater for smaller units, while higher up larger units are more attractive. Small apartments require more servicing and can be more difficult to access from a centralised core without losing saleable floor to circulation.

- Balconies become less desirable with height. More expensive solutions, such as recessed or winter gardens, tend to be used and this can significantly increase the building perimeter/area ratio.

- Use – single use buildings tend to be more efficient than multi-use buildings, as each function (e.g. hotel, office) will usually need its own entry and circulation In multi-use all buildings, space efficiency is determined by the distribution of functions. For example, a sky restaurant will require additional lifts that go to the top of the building. Stacking structures for different functions can require a complex structural transition to transfer loads, and may cause the structure to be less efficient or require the introduction of transfer structures, which can be a storey in height.

Construction

The health and safety of contractors, residents, maintenance staff, visitors and neighbours is paramount in the design of tall buildings. With over 60 years of experience, Chapman Taylor provides world-class technical expertise – ensuring compliance with current regulations and advising on global best practice to ensure our buildings are adaptable to meet future requirements and stand the test of time.

The construction of tall buildings takes on average, 28 months to complete¹, due to their technical complexity and the challenges of working in restricted city centre sites. Labour productivity on towers also tends to be less than on low-rise due to logistical factors and increased health and safety measures. To mitigate this, the construction method and sequencing should be considered very early in the design.

Mace has invested in a ‘jump factory’ – a 10-storey-high enclosure, inside which the construction of a complete multi-storey building takes place over five construction levels. What emerges as the factory is jacked up on a weekly cycle, delivering a newly constructed building which, from the outside, is complete, requiring only internal finishes. This rapid construction method enabled a 30% faster handover on the East Village No 8 building in Stratford, East London.

Structural design has traditionally been based on the well-tried concept of a central concrete core with sheer walls that double as apartment walls, and concrete slabs that address fire, acoustic, height and span requirements cost-effectively. However, there has recently been a shift to prefabricated construction. For example, Greystar is currently building two residential towers at 101 George Street in Croydon, which are claimed to be the world’s tallest modular buildings – it has been estimated that it will take two years to build, rather than the four needed when using traditional methods. The closely controlled factory process significantly reduces waste, requires fewer workers and provides higher quality and greater certainty on costs over time. The scheme consists of two concrete cores and 1,500 self-supporting modules.

Towers also need to be designed to facilitate adaptation, disassembly and repurposing to reduce waste and extend the building’s useful life, providing economic and environmental benefits for builders, owners, occupants and communities. At present, the tallest tower to be demolished in the UK (to make way for the Shard) was the 25-storey Southwark Towers. The typical way to demolish a building in the United Kingdom is by implosion – however, high-rise developments in dense urban environments tend to be dismantled manually.

The health and safety of contractors, residents, maintenance staff, visitors and neighbours is paramount in the design of tall buildings.

Summary

At Castle Park View, we have consciously designed to create the basis of a sustainable city centre community in a building which will become an instantly recognisable and welcome landmark in Bristol. We have done this by paying close attention to, and complementing, the site’s historic context, by ensuring that the design makes an attractive visual statement and, most importantly, by designing with the needs of the residents themselves at the heart of our thinking.

The UK needs a wide mix of building types to solve the housing crisis, and tall buildings will undoubtedly play an increasingly prominent role in the growth of its key cities. We are likely to see further development in London’s outer zones and in key cities with a growing rental market. This will present a significant challenge – to balance viability, by maximising efficiency, with providing new ways of living that encourage social interaction, and to provide homes that people want and can afford to live in.

Our experience in designing and delivering high-rise buildings coupled with our expertise in the modular construction and BtR sectors makes Chapman Taylor well-placed to meet this challenge.

¹ NLA London Tall Buildings Survey, 2019

*Areas of brownfield land, identified in the Mayor’s London Plan, with a significant capacity for development that can typically accommodate at least 5,000 jobs, 2,500 new homes or a combination of the two.